By Ernesto Castañeda, Daniel Jenks

President Donald Trump aims to upend the immigration system in the United States in his first few days in office. On Jan. 20, 2025, Trump signed various executive orders that temporarily prevent refugees from coming to the U.S. and block immigrants from applying for asylum at a U.S. border, among other measures.

Another executive order calls on federal agencies to not issue passports, birth certificates or Social Security numbers to babies born in the U.S. to parents not in the country legally, or with temporary permission. Eighteen states sued on Jan. 21 to block this executive order that challenges birthright citizenship, which is guaranteed by the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

We are scholars of immigration who closely follow public discussions about immigration policy, trends and terminology. Understanding the many different immigration terms – some technical, some not – can help people better understand immigration news. While not an exhaustive list, here are 10 important terms to know:

1. Migrant

A migrant is a person who moves from their place of birth to another location relatively far away. There are different words used to describe migrants and their particular circumstances. Internally displaced people, for example, means people who are forced to move within their own country because of violence, natural disasters and other reasons.

International migrants move from one country to another, sometimes without the legal authorization to enter or stay in another country. There are also seasonal or circular migrants, who often move back and forth between different places.

Between 30% and 60% of all migrants eventually return to their birth countries.

There is not much difference in why people decide to migrate within their own country or internationally, with or without the legal permission to do so. But it is easier for people from certain countries to move than from others.

2. Immigrants

The terms immigrants and migrants are often used interchangeably. Migration indicates movement in general. Immigration is the word used to describe the process of a non-citizen settling in another country. Immigrants have a wide range of legal statuses.

An immigrant in the U.S. might have a green card or a permanent resident card – a legal authorization that gives the person the legal right to stay and work in the U.S. and to apply for citizenship after a few years.

An immigrant with a T visa is a foreigner who is allowed to stay in the U.S. for up to four years because they are victims of human or sex trafficking. Similarly, an immigrant with a U visa is the victim of serious crimes and can stay in the U.S. for up to four years, and then apply for a Green Card.

An immigrant with a H-1B visa is someone working for a U.S. company within the U.S.

Many international students in higher education have an F-1 visa. They must return to their country of birth soon after they graduate, unless they are sponsored by a U.S. employer, enroll in another educational program, or marry a U.S. citizen. The stay can be extended for one or two years, depending on the field of study.

3. Undocumented Immigrants, Unauthorized Immigrants and Illegal Immigrants

These three charged political terms refer to the same situation: migrants who enter or remain in the country without the proper legal paperwork. People in this category also include those who come to the U.S. with a visa and overstay its permitted duration.

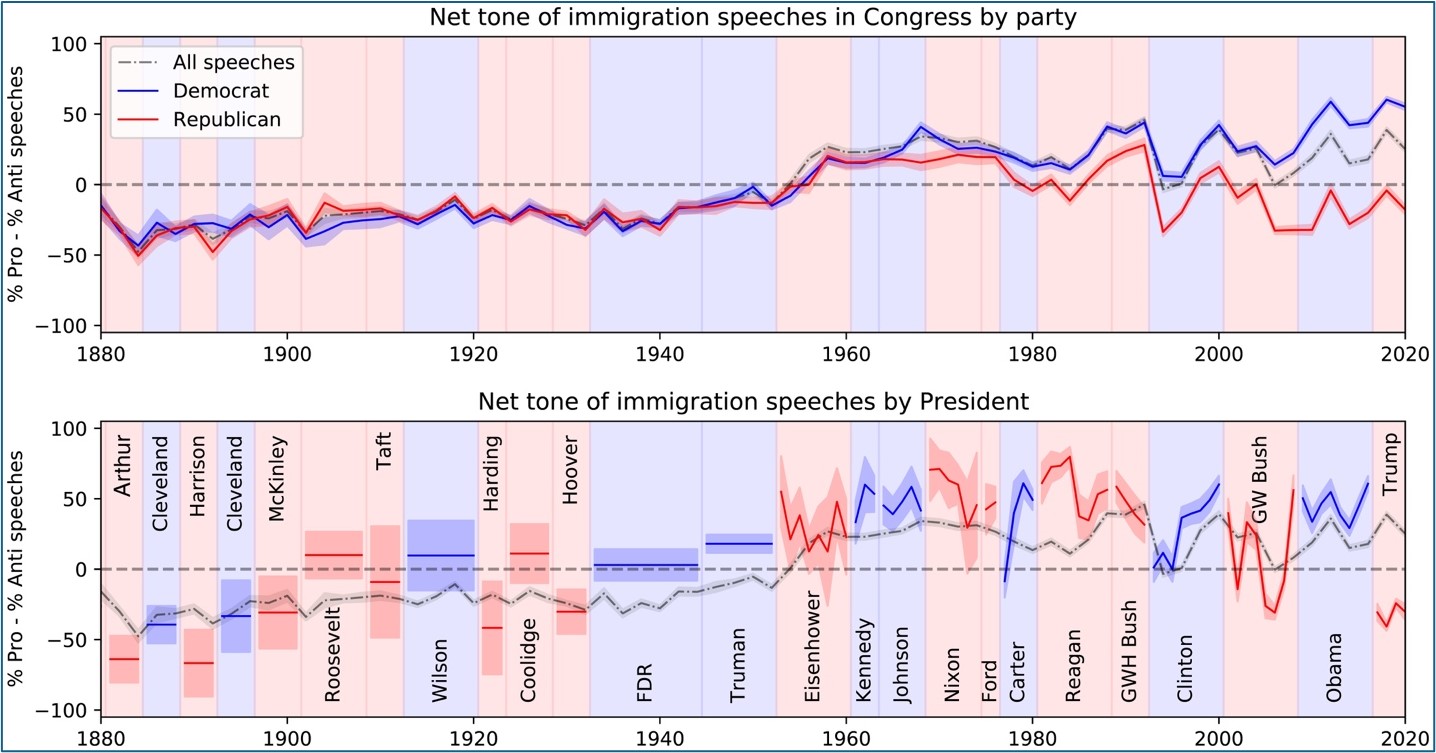

Some of these immigrants work for cash that is not taxed. Most work with fake Social Security numbers, pay taxes and contribute to Social Security funds without receiving money after retirement.

Immigrants without legal authorization to be in the U.S. spent more than US$254 billion in 2022.

4. Asylum Seekers

An asylum seeker is a person who arrives at a U.S. port of entry – via an airport or a border crossing – and asks for protection because they fear returning to their home country. An immigrant living in the U.S. for up to one year can also apply for asylum.

Asylum seekers can legally stay temporarily in the U.S. while they wait to bring their case to an immigration judge. The process typically takes years.

Someone is eligible for asylum if they can show proof of persecution because of their political affiliation, religion, ethnic group, minority status, or belonging to a targeted group. Many others feel they need to leave their countries because of threats of violence or abusive relationships, among other dangerous circumstances.

A judge will eventually decide whether a person’s fear is with merit and can stay in the country.

5. Refugees

Refugees are similar to asylum seekers, but they apply to resettle in the U.S. while they remain abroad. Refugees are often escaping conflict.

The Biden administration had a cap of admitting up to 125,000 refugees a year.

Refugees can legally work in the U.S. as soon as they arrive and can apply for a green card one year later. Research shows that refugees become self-sufficient soon after they settle in the country and are net-positive for the country’s economy through the federal taxes they pay.

6. Unaccompanied Children

This is a U.S. government classification for migrant children who enter the U.S. without a parent or guardian, and without proper documentation or the legal status to be in the country. Because they are minors, they are allowed to enter the country and apply for the right to stay. Most often, they have relatives already in the country, who assume the role of financial and legal sponsors.

7. Family Separation

This refers to a government policy of separating detained migrant parents or guardians from the children they are responsible for an traveling with as a family unit. The first Trump administration separated families arriving at the border as part of an attempt to reduce immigration.

At least 4,000 children were separated from their parents during the first Trump administration. The Biden administration tried to reunite these families, but as of May 2024, over 1,400 children separated during Trump’s first term still were not reunited with their families.

Legal migration systems that lack avenues for immigrants who work in manual labor to move with their families, and deportations, both also create family separations.

8. Immigration Detention

Immigration detention refers to the U.S. government apprehending immigrants who are in the U.S. without authorization and holding them in centers that are run similar to prisons. Some of these centers are run by the government, and others are outsourced to private companies.

When a U.S. Customs and Border Protection official apprehends an immigrant, they are often first brought to a building where they are placed in what many call a hielera, which means icebox or freezer in Spanish. This refers to cells, cages or rooms where the government keeps immigrants at very low temperatures with foil blankets and without warm clothing.

Immigrants might then be quickly deported or otherwise released in the country while they await a court date for an asylum case. Other immigrants who are awaiting deportation or a court date will be placed in an immigration detention center. Some must post bond to be released while awaiting trial.

9. Coyote

A coyote is the Spanish word for a guide who is paid by migrants and asylum seekers to take them to their destination, undetected by law enforcement. Coyotes used to be trusted by the migrants they were helping cross into the country. As the U.S. has tried to make it harder to enter illegally, the business of taking people to and across the U.S.-Mexico border unseen has become more expensive and dangerous.

10. The Alphabet Soup of Government Players

The Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, is a law enforcement agency created after 9/11. It includes a number of agencies that focus on immigration.

These include U.S. Customs and Border Protection, or CBP, an agency that is in charge of collecting import duties, passport and document controls at airports, ports, and official points of entry along the border.

The Border Patrol is a federal law enforcing agency under CBP in charge of patrolling and securing U.S. borders and ports.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement, or ICE, is a branch of DHS that works within the U.S., within its borders, focusing on detaining and deporting immigrants.

The Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS, takes care of unaccompanied minors after they enter the country.

Ernesto Castañeda is the Director of the Immigration Lab and the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies and Professor at American University.

Daniel Jenks is a Doctoral Student at the University of Pennsylvania,

This piece can be reproduced completely or partially with proper attribution to its author.