By Joseph Fournier, Bennett Donnelly, and Ernesto Castañeda

April 22, 2025

Anti-immigrant sentiment has been a salient theme in both American political and social discourse. Nativism enjoys periodic spikes in popularity. Legislation such as the draconian Immigration Act of 1924 dot the immigration policy landscape. One hundred years later, we find ourselves in an eerily similar position.

A successful political party, movement, or organization must have clear messaging in order to garner public support. Republicans have incarnated themselves as the party of contemporary nativism. This has resulted in a shift rightward regarding public discourse on immigration. Some Democrats have followed suit, with for example, some candidates supporting border wall construction as elections drew nearer.

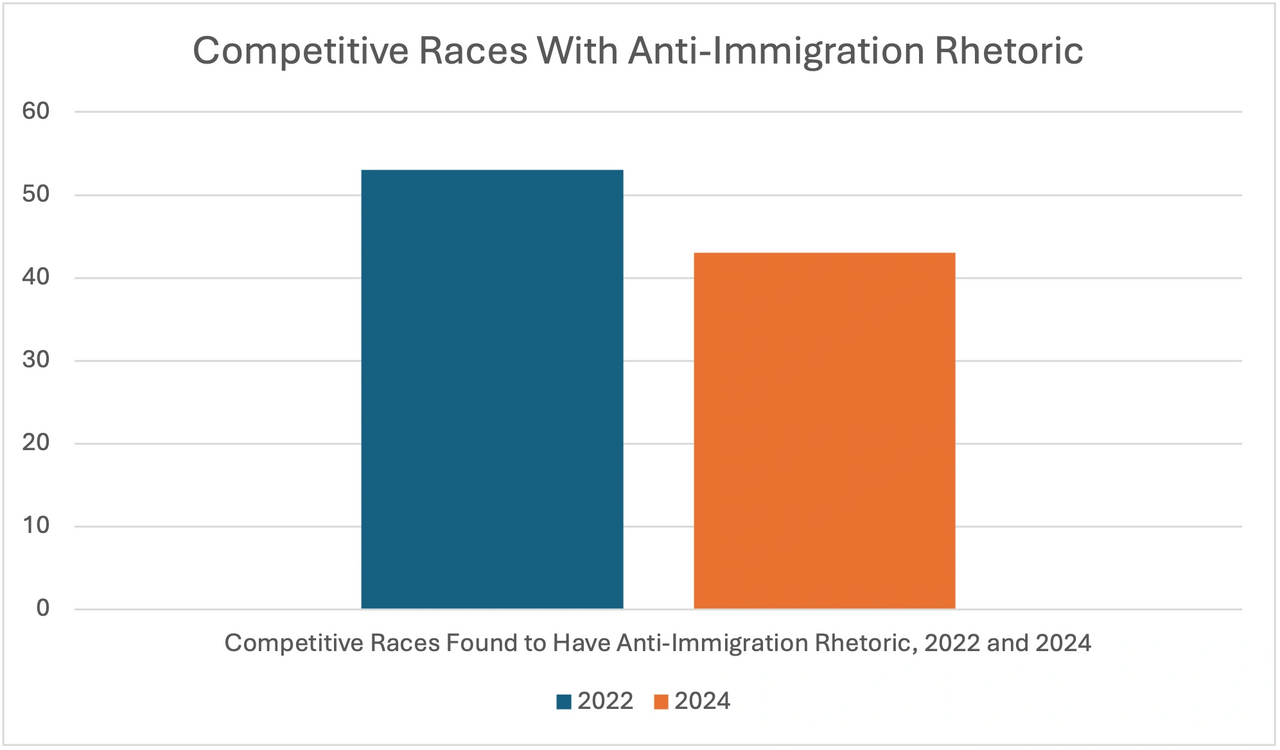

In 2022, there were 77 competitive races (where either party won by less than 10%). In 2022, there were 53 campaigns with anti-immigrant rhetoric in their official materials (campaign websites, social media posts, and TV and YouTube ads). In 2024, there were also 77 competitive elections, with 43 having anti-immigrant rhetoric in their campaign materials. So, anti-immigrant discourse as a main campaign issue dropped from 69% to 56% among Republican candidates in competitive races (see Figure 1).

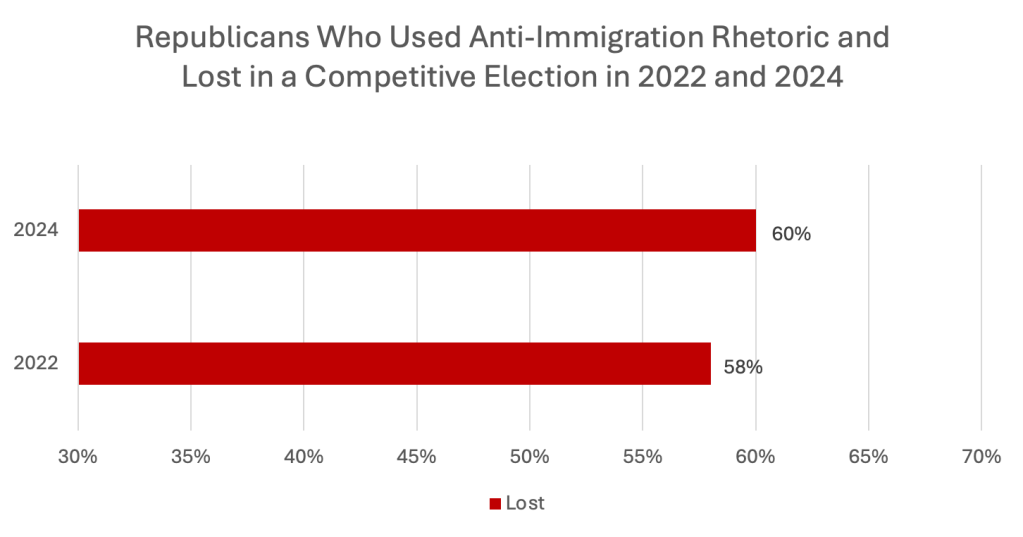

In 2024, campaigns that employed anti-immigrant rhetoric had a win-loss ratio similar to 2022.

The presence of anti-immigrant sentiment among Republican campaigns fell from 2022 to 2024. While such rhetoric flourished in Trump’s presidential campaign, it was less present in House, Senate, and gubernatorial races. When anti-immigrant rhetoric was present, it ended in failure more often than victory. From this, we could deduce that people are less concerned about immigrants in their communities. Instead, they seem to be more concerned about border security and immigration on the national scale.

Figure 2, “Republicans Who Used Anti-Immigration Rhetoric with Election Results, 2022 and 2024”

In 2024, the Republican message emphasized migration as a security issue, rather than an economic or humanitarian one, arguing that immigration should be treated with the same urgency as any other potential foreign enemy. Migration is framed as a security issue through negative rhetoric surrounding the supposed criminality of migrants, such as the newly coined term “migrant crime,” used extensively by Republicans on the campaign trail. This term is a clear attempt to predetermine the culpability of migrants coming into the US and frame them as criminals, or even as invaders and terrorists, though not so much in competitive races.

Many Republican campaigns may disguise nativist sentiments under the guise of national security concerns. Border security narratives help reinforce anti-immigrant ideas that historically portray migrants, especially Latinos, as criminals or invaders. This ambiguous messaging may explain why many Trump voters did not believe he would legitimately carry out many of his campaign promises regarding mass deportations.

Republican parties promote border security and anti-immigrant discourse from the top down, reducing the need for individual House candidates to explicitly state their views towards immigration. With border securitization becoming a mainstream policy promoted by figureheads on both sides, down-ballot candidates can avoid directly addressing issues like immigration and border walls in their campaigns. By aiming to associate immigration with national defense, the “border crisis” is fabricated to be an existential threat. Oftentimes incendiary rhetoric is used to obfuscate what is real from unreal.

We identify a pattern across the Republican tickets, where candidates with military backgrounds tend to use anti-immigrant rhetoric justified by their experience in the military as evidence for their security concerns (Jay Furman TX–28, Laurie Buckhout NC–1, Mike Garcia CA-27). Evidently, using the facilities at Guantanamo Bay to house migrants reinforces the misconception many Republican candidates echo in their campaigns that migrants are security threats. This also contributes to why top party members, such as Ted Cruz and Donald Trump, used exceptionally strong anti-immigrant rhetoric to make down-ballot candidates more acceptable and mainstream where necessary, while maintaining the same broader party message.

For moral, ethical, and strategic reasons, Democrats should speak openly against anti-immigrant rhetoric. The threat of anti-immigrant rhetoric itself is a real threat, but data shows that the average American voter tends to be indifferent or in favor of immigration, especially at the local and state levels. The political mechanisms that produce this rhetoric have a firm grip on the mediascape that influences national elections, but when it comes to their own communities, voters trust their own eyes and lived experiences about how the immigrants they know are not that much different from themselves.

Joseph Fournier and Bennett Donnelly are Research Assistants at the Immigration Lab. Ernesto Castañeda, PhD is the Director of the Immigration Lab at American University.