By Juan A. Bogliaccini, Professor of Political Science, Universidad Católica del Uruguay

This small South American country is seeking new markets and investment while remaining anchored to MERCOSUR and balancing ties with the United States and China.

For more than three decades, Uruguay’s strategy for international economic integration has revolved around the Southern Common Market, MERCOSUR. Founded in 1991 by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay, the bloc emerged at the end of the Cold War with the goal of deepening regional economic integration and strengthening trade among its members. For Uruguay, a small country of just over three million people located between two regional giants, the bloc initially proved highly beneficial. During the 1990s, MERCOSUR became the main engine of Uruguayan exports and foreign investment.

That dynamic began to shift at the end of the decade. Brazil’s currency devaluation in 1998 and Argentina’s financial collapse in 2001 exposed the vulnerabilities of Uruguay’s economic dependence on its neighbors. At the time, a majority of the country’s exports was destined for these two markets, and the crises had profound effects on Uruguay’s economy.

These events triggered a long-running debate within the country’s political and economic elites about the future of Uruguay’s international trade strategy. At the center of the discussion was one of MERCOSUR’s key institutional rules: member states cannot negotiate individual free trade agreements outside the bloc. Critics argued that this constraint limited Uruguay’s ability to diversify its economic partnerships in an increasingly globalized world.

For many years, much of the political center-right advocated a strategy similar to that pursued by Chile—signing bilateral free trade agreements across multiple regions of the world. The center-left generally defended remaining firmly within the regional framework, emphasizing the importance of political and economic integration with neighboring countries.

Over time, however, both sides gradually converged toward a more pragmatic position. Today there is broad consensus that Uruguay should remain in MERCOSUR while pushing for greater flexibility within the bloc allowing for members to pursue complementary trade agreements. In practice, leaving MERCOSUR has never been a realistic option. Brazil and Argentina remain crucial trading partners, particularly for exports linked to regional value chains and cross-border production networks.

At the same time, the bloc itself has increasingly sought to expand outward. In recent years, MERCOSUR has concluded trade agreements with Singapore and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which includes Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, and Switzerland. In 2026, after more than twenty-five years of negotiations, MERCOSUR also finalized a landmark trade agreement with the European Union. Across successive governments representing different political parties, Uruguay has consistently supported these negotiations as part of a long-term strategy of gradual trade opening.

Meanwhile, Uruguay’s broader trade relationships have evolved significantly. Over the past two decades, China has become the country’s principal destination for goods exports, particularly agricultural commodities such as soybeans and forestry products like cellulose pulp. At the same time, the United States has become the main market for Uruguay’s rapidly growing service sector, especially software development and business services.

These trends have positioned Uruguay within a complex global landscape shaped by growing geopolitical competition between the world’s two largest economies. Rather than aligning strongly with either side, successive Uruguayan governments have sought to maintain a careful balance between Washington and Beijing while preserving strong ties with their regional partners.

Recent administrations have also attempted to broaden the country’s commercial horizons. During the presidency of Luis Lacalle Pou (2020–2025), Uruguay applied to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), one of the world’s most significant multilateral trade agreements. Although accession negotiations are only beginning, the move signaled Uruguay’s intention to deepen economic ties with Asia-Pacific markets.

The Lacalle Pou government also explored the possibility of negotiating a bilateral free trade agreement with China. While the initiative ultimately did not move forward—largely because Beijing made clear it preferred negotiations with MERCOSUR as a whole—the effort served an important political purpose. Alongside the negotiations with the CPTPP, it signaled to Uruguay’s regional partners that the country was determined to pursue broader trade opportunities.

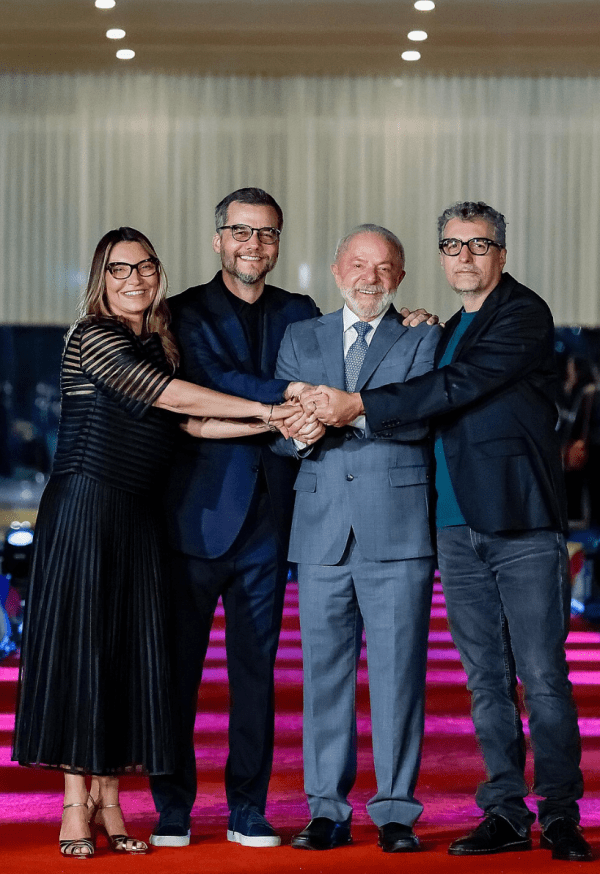

The current administration of President Yamandú Orsi has continued this strategy of balanced engagement. Diplomatic outreach to both the United States and China reflects Uruguay’s pragmatic approach in an increasingly multipolar global economy. Promoting exports has become particularly important as the strength of the Uruguayan peso makes international competitiveness more challenging for domestic producers.

Despite these global ambitions, Uruguay’s integration into international value chains remains heavily regional. Much of the country’s participation in global trade occurs through “import-to-export” production models, particularly in agro-industrial sectors that rely on imported inputs and regional processing networks. A large share of these exports continues to be destined for MERCOSUR markets, reflecting the enduring importance of regional economic integration.

This structural reality explains why Uruguay’s leaders have consistently pursued a dual strategy: maintaining strong economic ties with Argentina and Brazil while simultaneously seeking new markets and investment partners around the world.

The recently concluded trade agreement between MERCOSUR and the European Union may represent an important step in that direction. Together with the agreements with Singapore and EFTA—and the expected accession of Bolivia to MERCOSUR—the deal could gradually expand the economic horizons of a country that remains heavily dependent on a limited number of export sectors.

For Uruguay, the stakes are significant. Since the end of the global commodity boom in the early 2010s, economic growth has slowed. As a result, it has become more difficult to reduce a fiscal deficit that hovers around 4 percent of GDP while public debt continues to rise gradually. Expanding exports and attracting foreign investment have therefore become central priorities for policymakers.

Yet Uruguay’s small domestic market inevitably limits its appeal to international investors. The country’s greatest economic asset lies instead in its potential role as a stable regional hub within the much larger South American market. With strong institutions, political stability, and relatively high levels of human capital, Uruguay often presents itself as a reliable gateway for companies seeking access to the region.

Realizing that potential, however, will require more than trade agreements alone. Expanding Uruguay’s global economic presence will depend on developing new productive sectors, increasing productivity in existing industries, and moving gradually toward exports with higher value added.

For a small country navigating between two regional giants and competing global powers, this is no simple task. But Uruguay’s strategy remains clear: maintain its regional anchor while steadily expanding its reach into the global economy.