By Ernesto Castañeda

September 27, 2024

On the morning of September 9, 2024, a Republican voter called into C-SPAN’s Washington Journal and said, “Democrats used to be all about the workers, but now it’s just socialism.” This short piece is respectfully directed to those who may share that sentiment. First, it’s important to note that, in principle, socialism is centered around workers, but it asks that workers own the companies they work at. Democrats are not socialists. Even the party’s most progressive figures, like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), identify as Democratic Socialists and advocate for the U.S. to adopt some of the social safety nets seen in Northern European countries and fight monopolies and for workers’ rights to create a tempered capitalism. Now, let’s turn to the real concerns about the economy as we approach the upcoming elections.

The economy is doing well

The U.S. economy is objectively performing very well, largely due to the Biden-Harris administration’s adoption and successful implementation of policies championed by figures like Sanders, Warren, and AOC. Compared to other countries, the U.S. has recovered more quickly from the pandemic’s effects, which were driven by lockdowns, labor shortages, and disruptions to global supply chains—all of which contributed to inflation. These policies, alongside immigration, have supported healthy economic growth. Notably, inflation and interest rates are decreasing without the economy slipping into a recession—an almost ideal outcome often referred to as a “soft landing.”

Nonetheless, some citizens and commentators still insist that the economy is weak, and voters often mention “the economy” as their main concern.

A shift in expectations on the economy

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, it was already common for millions of Americans to live paycheck to paycheck and carry significant debt. The pandemic, however, reshaped Americans economic expectations in at least three important ways: 1) The imminent threat to life placed greater value on human life and people’s time; 2) It exposed our heavy dependence on foreign producers, global supply chains, and essential local workers; and 3) It led to a bipartisan recognition that the government can and should take action to address hunger, unemployment, public wellbeing, inequality and support the working and middle class, as well as small and large business and postpone evictions in times of collective suffering.

Let me elaborate on point three. The economic policies and incentives—such as support for businesses both large and small, direct checks to families, and the child tax credit—implemented in a bipartisan effort during the pandemic by both the Trump-Pence and Biden-Harris administrations significantly raised economic standards and cut child poverty in half. These policies also reflected what C. Wright Mills advocated in the 1960s: when unemployment is widespread, it should be viewed as a social issue rather than a matter of personal responsibility, worth, or morality. In contrast to the neoliberal focus on market fundamentalism, these pandemic-era measures revived Keynesian principles, emphasizing a return to full employment and expanding support for policies reminiscent of FDR’s New Deal—where the government plays a role in reducing inequality and supporting the working and middle class.

The real cause of frustration

One of Joe Biden’s boldest and most significant accomplishments may have been his repeated assertion that “trickle-down economics has never worked. It’s time to grow the economy from the bottom up and the middle out.” This is a change in the long-held belief in individualistic ideologies, such as the notion of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.” Stemming from this ideological shift, I believe much of the unease felt by the working and lower-middle class about “the economy” stems from frustration over the end of many pandemic-era cash transfers and stimulus checks, which were initiated by both the Trump and Biden administrations. These transfers and the forced savings due to the lockdowns allowed some families to pay credit card debt and even increase their savings, which for many are now depleted again.

Ironically, it was the Republican Party that blocked the extension of the child tax credit, a key measure backed by Democrats to support working families. Yet, many voters remain unaware of this. Meanwhile, tax-evading billionaires, including figures like Trump, exacerbate the economic challenges rather than providing solutions. A modest increase in taxes on billionaires would help fund essential programs like the child tax credit, and contrary to popular rhetoric, this is not socialism—it’s a practical approach to ensuring fair contributions from the wealthiest.

Outdated and Misguided Economic Narratives

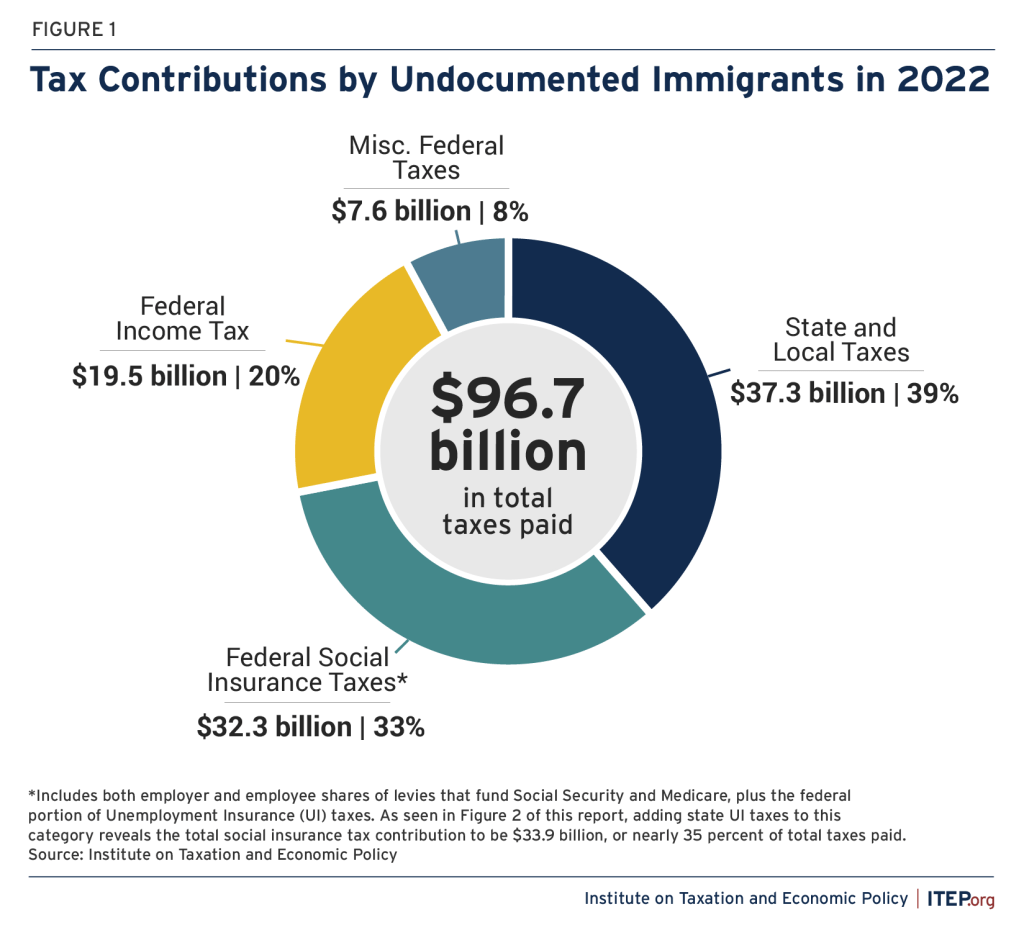

Trump has attempted to link his scapegoating of immigrants to the current economic challenges, falsely claiming that immigrants are taking jobs from those most in need, particularly African Americans, Hispanics, and union workers. However, this argument does not hold up—unemployment rates are low, and wages are rising. As a result, most people are unlikely to be swayed by this rhetoric. Those who do buy into it likely already held anti-immigration views prior to the pandemic and/or are victims of structural changes stemming from Reaganomics.

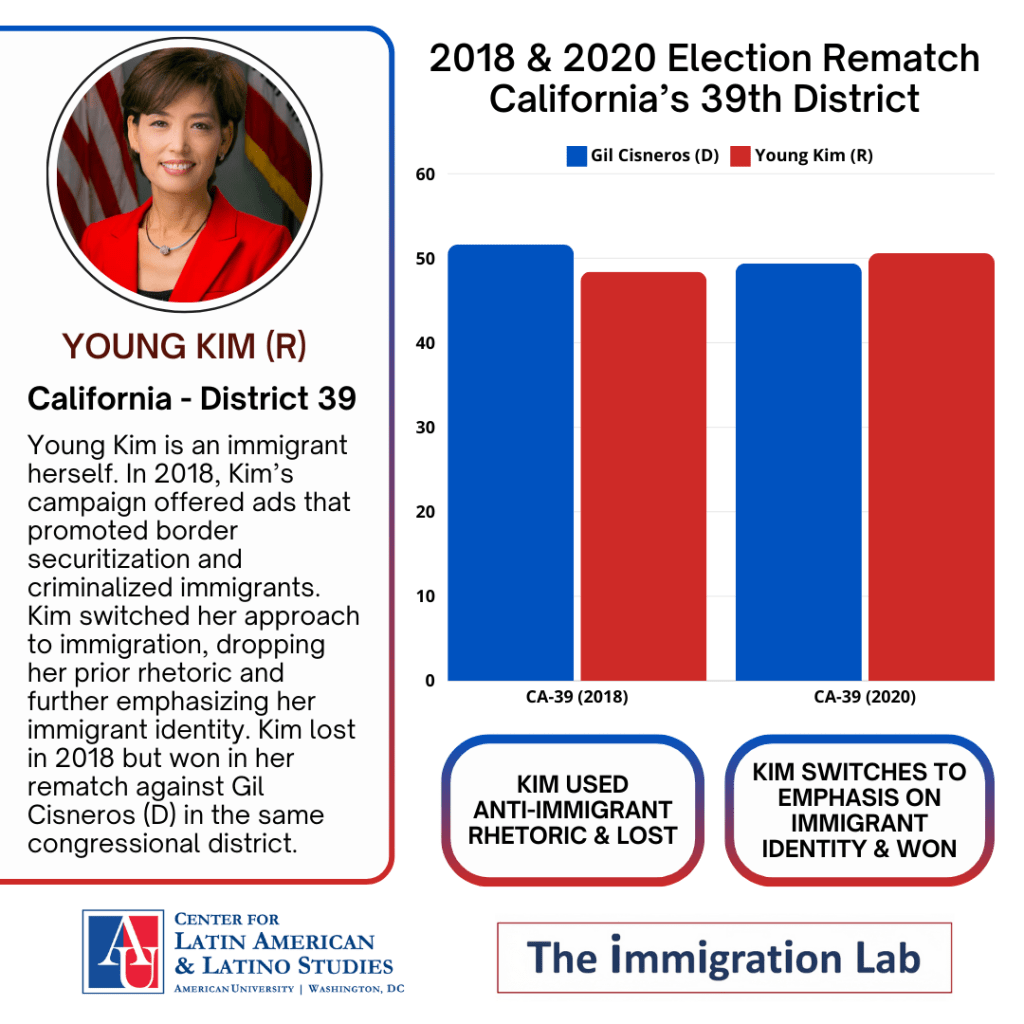

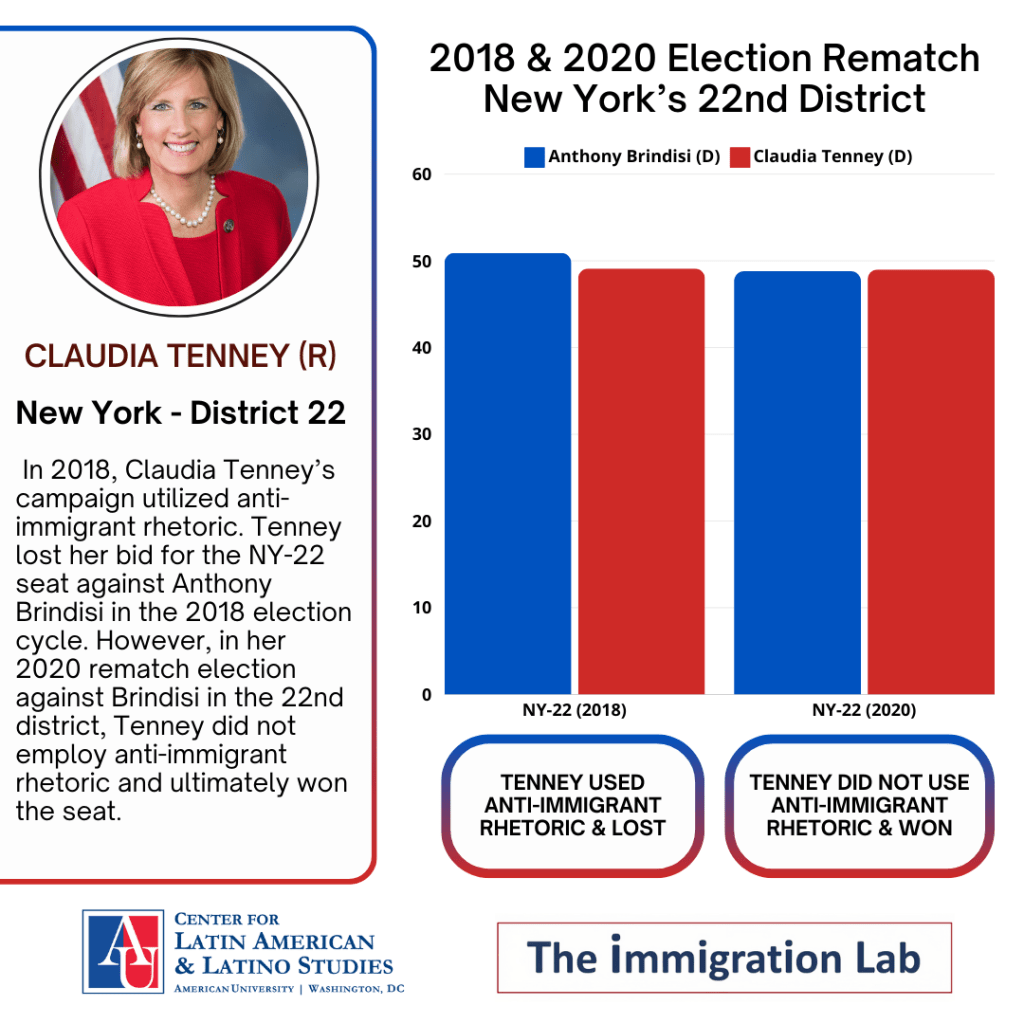

By invoking fears that the U.S. could become “like Venezuela,” Trump taps into concerns among immigrants who lived Venezuela’s prosperity before Chavismo or those fleeing other authoritarian regimes. However, Republicans risk losing these voters by frequently portraying Venezuelan immigrants as criminals—members of the Tren de Aragua gang—or as individuals released from prisons and mental institutions by Maduro and sent to the U.S. This narrative echoes real historical events such as Cuba’s Marielitos or British prisoners sent to Australia as settlers, as well as xenophobic stereotypes and prejudices once directed at Irish, Italian, and Mexican immigrants. History, however, shows that the children of immigrants often experience rapid social mobility and thus contribute as much, if not more, to society than the children of native-born citizens.

Some attempt to alarm undecided voters by claiming that Harris is advocating for price controls. In reality, she is focused on preventing monopolies and negotiating better prices when the government buys in bulk, as demonstrated successfully with insulin. This pragmatic approach has broad support across Republicans, Democrats, and Independents. Harris and Walz are not pushing radical leftist ideas; rather, they are promoting a moderate populism that is not linked to exclusionary Christian nationalism.

“Opportunity economy”

In her speech at the Economic Club of Pittsburgh on September 25, 2024, Harris stated:

“The American economy is the most powerful force for innovation and wealth creation in human history. We just need to move past the failed policies that have proven not to work. And like generations before us, let us be inspired by what is possible. As president, I will be guided by my core values of fairness, dignity, and opportunity. I promise you I will take a pragmatic approach. I will engage in what Franklin Roosevelt called bold, persistent experimentation, because I believe we shouldn’t be constrained by ideology but instead pursue practical solutions to problems.”

With this statement, she invoked FDR’s legacy while offering a centrist, pragmatic vision for addressing the economic challenges facing Americans.

While some commentators argue that Harris and Walz haven’t provided enough details on their economic policy, they are actually offering a balanced approach that appeals to both corporations and small businesses. Their plan promotes U.S. manufacturing and nearshoring, aims to reduce the climate impact of production and consumption, and provides much-needed support to the low and middle class in regions hit hardest by deindustrialization. Trump talks much about caring about the working class but did little to benefit them structurally and long-term while in the White House. Policies like exempting tips and overtime from taxation fit within Harris’ framework, but Harris also advocates for more ambitious measures to really level the economic playing field a bit more. Harris calls this vision the ‘opportunity economy,’ a pragmatic approach to economic and industrial policy that many former Bernie and Trump supporters could, in principle, support.

Ernesto Castañeda PhD, Director of the Immigration Lab and the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies, American University in Washington DC.

Edited by Robert Albro, CLALS Associate Director of Research, and Edgar Aguilar, International Economics master’s student at American University.

This piece can be reproduced completely or partially with proper attribution to its author.