By Ernesto Castañeda

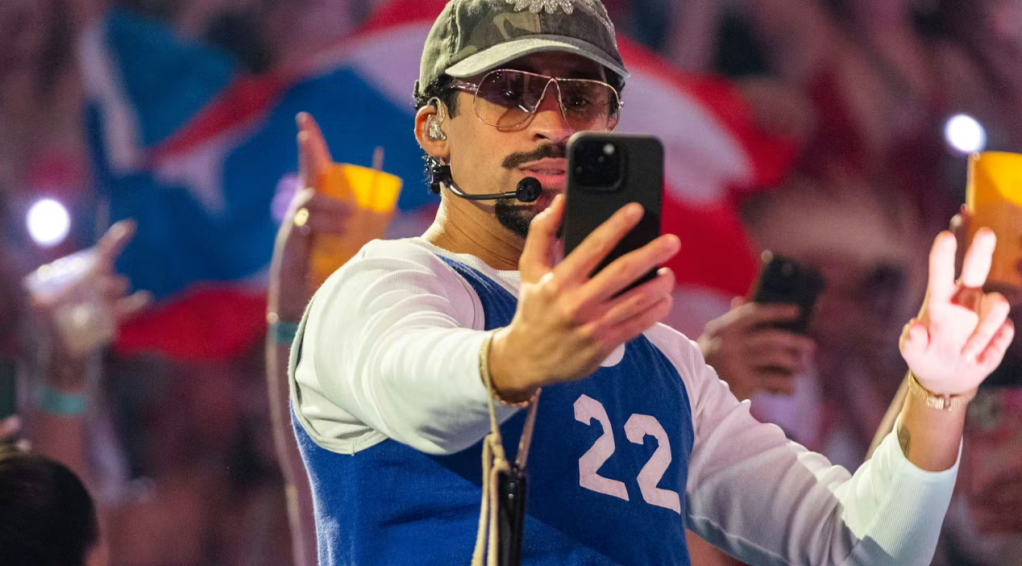

Bad Bunny’s halftime performance showed how much Latinos love America, even if some parts of America do not love them back. Performed mostly in Spanish, it showed the reality that Latinos and Spanish are part of America’s culture: its history, its present, and its future. As the performance’s references to salsa and Ricky Martin’s participation in it reminded us, Latinos’ contributions to U.S. and global culture are not a new phenomenon.

Performances like this weaken MAGA’s ideological project even without any direct references to the current administration. Most importantly, they are a reminder of what most people can see: that Latinos, Asians, and Africans are part of U.S. communities, schools, labs, and the art and music scenes.

That is why most people in the U.S. were against ICE and mass deportations before the Super Bowl halftime show. But the humanization of Puerto Ricans and brown people could have reached and created empathy or even admiration among some people who were on the fence, do not follow the news, or live in areas with few immigrants.

When Bad Bunny was announced, some said they would boycott, that ICE would be present and carry out mass arrests, that people would not watch the show, or that it would go badly. None of that happened. The hate and fearmongering just made Bad Bunny’s performance even more special and powerful.

The performance’s positive message about love and inclusivity is a strong antidote to the fear created by ICE operations and the hatred induced by anti-immigrant, anti-Latino, and anti-black discourse. As a Puerto Rican, Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, aka Bad Bunny, is a U.S. citizen. However, like many other minorities, on the street, he is racialized and treated as having fewer rights and valid political claims than white citizens who speak English as their first language.

Trusting his team to catch him after he fell backwards from the roof of the casita is a good metaphor for how he knew that Puerto Ricans, Latinos, immigrants, and Americans would have his back, despite the death threats against him that forced him to wear a bulletproof vest during the Grammys ceremony. The community was able to celebrate with him and through him as they watched the Super Bowl during a challenging time. Thus, in his own eyes, his music, lyrics, and his political statements against colonialism, calling Puerto Rica trash, and the dehumanization of people of color and the risks this entails, are worth it.

The halftime show made Latino kids and teenagers feel proud of who they are. It also made many Latinos and non-Latinos, whether they speak Spanish or not, proud of their musical tastes. Some of their parents or grandparents may not have known Bad Bunny’s music, but his fans are not alone. Bad Bunny recently won the Grammy for Album of the Year. He is the most-streamed artist globally on Spotify and other platforms, and the Super Bowl halftime show was enjoyed by over 130 million live viewers, plus over 80 million replays on the NFL YouTube page. This is as close as any cultural act can come to entering the U.S. and global mainstream.

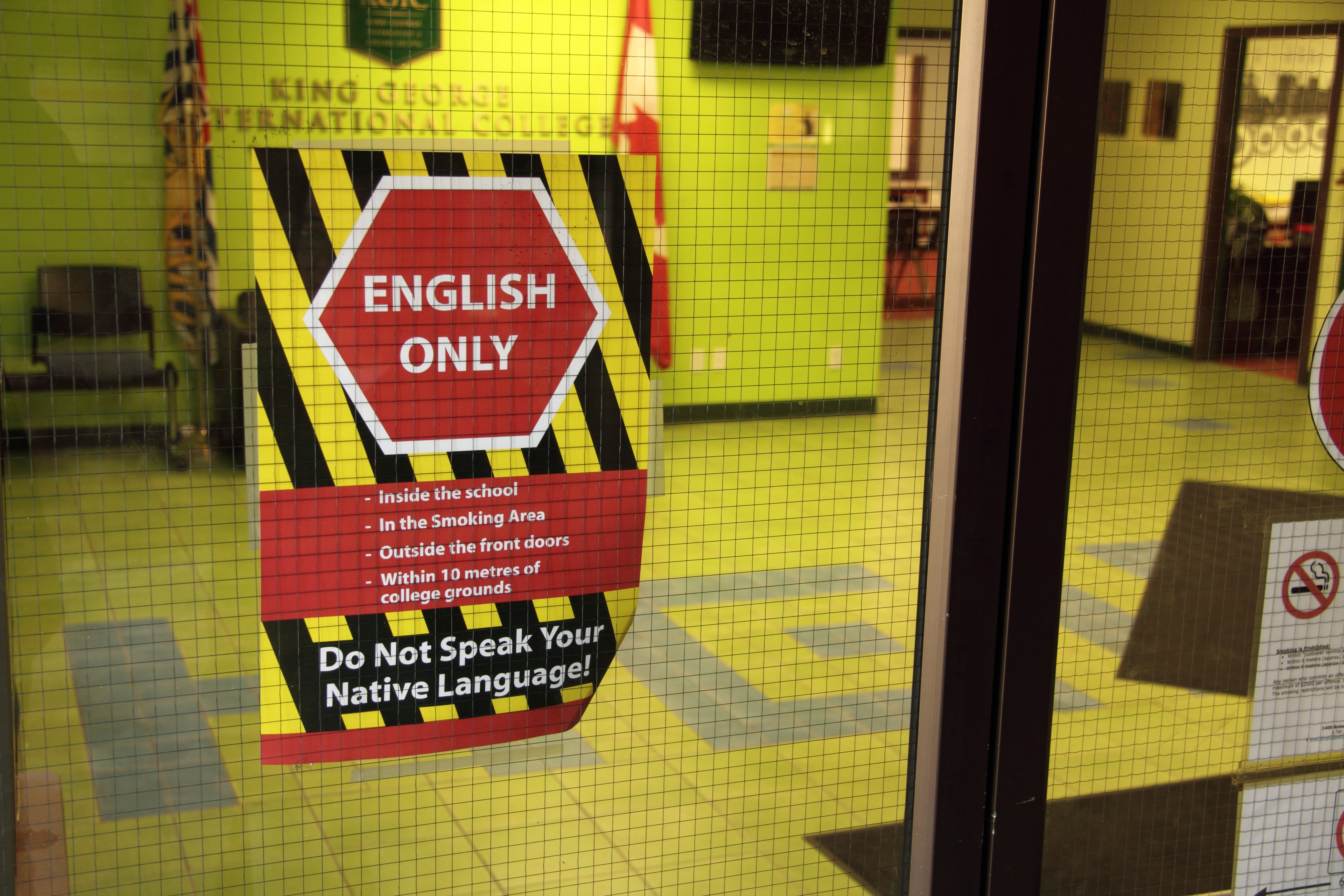

That is why the NFL selected the world’s leading artist. Bad Bunny is popular worldwide, singing in Spanish. He has no shame about his native language, accent, lingo, or culture. He is proudly Puerto Rican, which makes him emblematic of this multicultural reality.

MAGA proposes that these types of performances threaten US culture. But the USA is stronger than MAGA thinks. It is strong because of its diversity and its mixing of elements from around the world into new, creative products that sell very well.

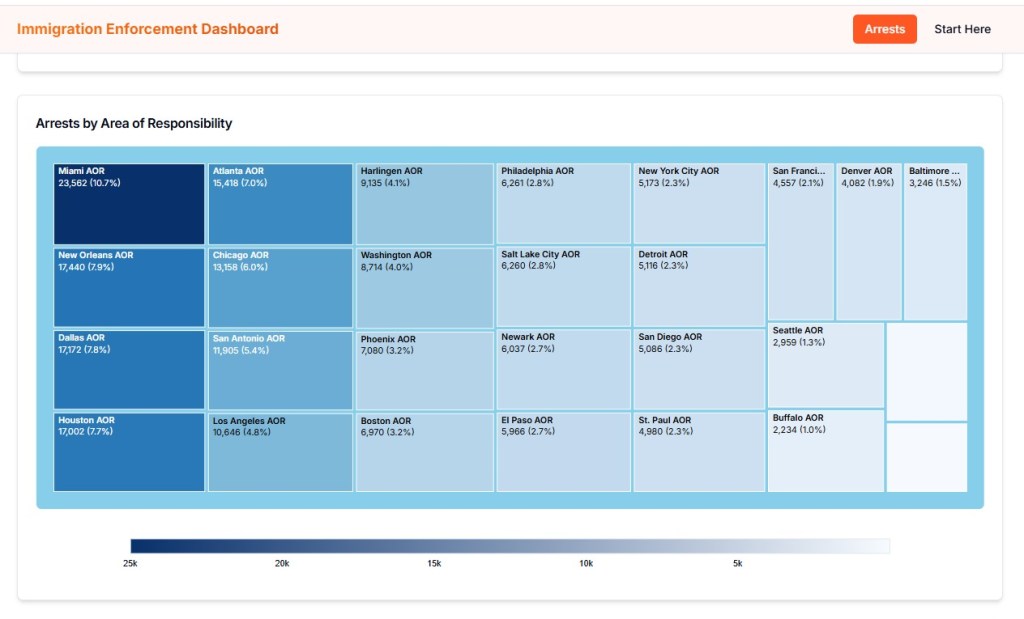

As I told Univision News, soon after Bad Bunny was announced as the performer for Super Bowl LX, and after he had hosted SNL and addressed the controversy the announcement caused, sending ICE to the Super Bowl would not have changed our multicultural reality; though it would have represented the fact that ICE and CBP act as if immigration equals crime. Santa Clara, California, is in the San Francisco Bay Area, where many residents were born abroad and work at Silicon Valley’s corporations. Thus, it would have been very difficult for ICE to patrol the streets around the Levy Stadium. Furthermore, it would have been economically and politically expensive if a large ICE operation in or around the stadium had caused the Super Bowl to start later or be severely understaffed.

When criticized by conservatives for being selected, Bad Bunny defended himself. In doing so, he also indirectly defended other Latinos who are not as famous as he is, but who also contribute in their own way to daily life in the U.S.A.

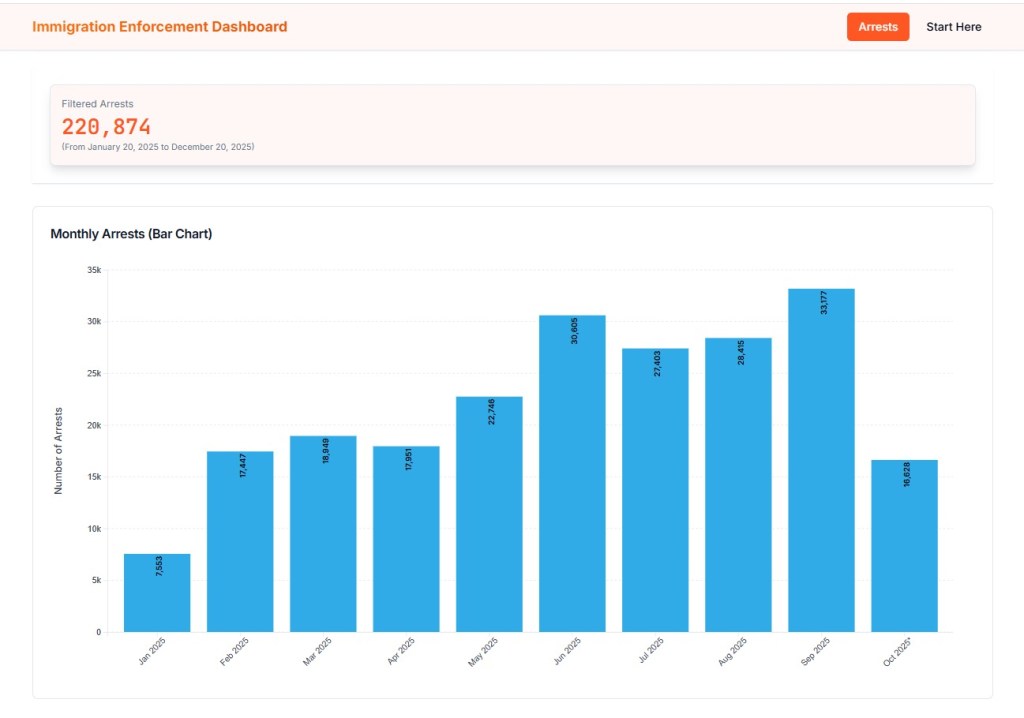

The U.S. continues living a practical contradiction on the one side being dependent on immigrant labor for affordability and economic growth but also complains about people arrivie to work and study. On the one hand, we have ICE detaining people for speaking Spanish, for being Latino, and hundreds of thousands of deportations happening. On the other hand, we have Latinos, the majority of whom are American citizens. Latinos are part of the economy, of culture, and of music. In the case of Bad Bunny, they make America great.

All Puerto Ricans are citizens because Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory. Nevertheless, many assume that being American means being white and speaking English without an accent, which is not true. There are U.S. citizens of all origins, races, skin colors, faiths, and mother tongues. This Super Bowl halftime show was a celebration of that diversity, which makes us strong. Bad Bunny was not out of place in the Super Bowl, but much discrimination against Latinos includes the belief that Latinos are not one hundred percent American.

The upset from MAGA spokespeople is because they do not have control over popular culture. They would like corridos and songs in all genres to be written in celebration of Trump. However, with a few rare exceptions, this is not the case.

People vote every few years, but they listen to music every week. The “culture wars” are not what Fox News says they are. Fox and other right-wing organizations politicize social issues that are at the early stages of the popular opinion shifts that ultimately lead to social change. No cultural product is loved by one hundred percent of the public. Culture is about practice, consumption, and remixing. People choose what type of food, music, and movies to consume time and time again. In recent years, Pedro Pascal, Diego Luna, Oscar Isaac, Benicio del Toro, Marcelo Hernández, Zoe Saldana, Ana de Armas, Rosario Dawson, Sofia Vergara, to name a few, have played key roles in some of the most popular movies and shows.

The takeaway is that Latinos are an important part of the United States and make cultural contributions that benefit the whole world. Besides many transnational influences, collaboration with other artists based in the U.S. and throughout the Americas creates a new cultural reality. This cultural reality is a blend of contributions from Latinos and other U.S.-based artists. Together, we are all stronger, and our music is more universal, as the broad national and international appeal of Bad Bunny’s performance clearly shows.

Ernesto Castañeda is a political, social, and cultural analyst.