By Robert Albro

Embed from Getty ImagesLatin American cities are powerful engines for growth, but sustaining that progress will require moving workers from the informal into the formal sector. Latin America is the most urbanized continent in the world, and its cities are now the region’s main economic engine. Its ten largest cities account for about half of the region’s economic output, and their share of economic activity is projected to increase by 2025. They are also increasingly aspiring to insertion in the global economy. And mayors often assume a CEO-like autonomy in attracting international capital, business, and talent to their cities, while pursuing policies designed to enhance their municipal standing as critical global nodes, hubs or platforms of innovation, manufacturing and services. Strategies include international city-to-city cooperation, corporate and multinational partnerships to fund infrastructure, global policy forums for mayors to share best practices regarding sustainability or climate change, and new urban planning intended to increase connectedness to global information flows. Citi and the Wall Street Journal in 2013 judged Medellín, Colombia, the “most innovative city” in the world. San José, Costa Rica, has become a telemarketing outsourcing center, in large part because of its well-prepared workforce. And cities like Monterrey, Mexico, and Curitiba, Brazil, are emerging tech hubs.

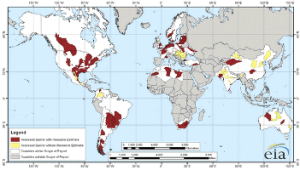

Over the last several decades, however, rapid urban growth in Latin America has also greatly expanded the urban informal sector. With sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America has the largest informal sector in the world. Of all workers in greater Bogotá, for example, 59 percent operate in the informal economy. Low levels of technology, finance and job skills conspire to limit productivity and to distance Latin America from the frontiers of the global economy. Along with low earnings and the lack of social benefits or income security, a large informal labor sector generates inadequate tax revenue for municipalities and chronic underinvestment and neglect of urban infrastructure. Pervasive informality also contributes to social exclusion. More than 80 percent of the top 50 most violent cities in the world are in Latin America, and this violence is concentrated along rapidly expanding urban margins. In the absence of resources from municipal authorities, marginal urban dwellers turn to illicit actors and activities for unregulated or pirated services and protection. Potentially competitive enterprises are hesitant to establish a presence in cities where property ownership is contested or where government voids leave land, money, governance and other resources, vulnerable to criminal capture.

Latin America’s cities aspire to effective insertion into the global economy while also struggling with very local and hard-to-change challenges of informality and unregulated urban growth. Labor flexibilization and privatization, hallmarks of 1990s-era neoliberal policies, at once promote the growth of the informal economy and complicate urban planning intended to facilitate the development of assets necessary for global competitiveness. Urban planners mistakenly continue to treat participants in the informal economy as a transient reserve army of labor composed of rural in-migrants not yet absorbed into the industrial sector. Yet if cities want to develop their niche in the global economy, policy makers will also have to attend to the connections between urban informality and social exclusion. Large-scale and violent protests, such as last year’s flash mob protests in shopping malls by working-class Brazilian youth, are demanding their “right to the city.” The economic future and competitiveness of Latin America’s cities significantly depends upon their capacity to address the second-class citizenship of their informal workforce. Overcoming social exclusion is a first step to competing effectively in a global economy characterized by increasingly stiff competition among cities.