By Ilka Treminio-Sánchez, Political Scientist of the University of Costa Rica.

The national elections held in Costa Rica on February 1, 2026, marked a turning point in the country’s recent political trajectory. Contrary to expectations of a runoff—common in a highly fragmented party system—the ruling party candidate, Laura Fernández, won in the first round with 48.3 percent of votes counted. This result not only ensured the continuity of the political project championed by President Rodrigo Chaves but also consolidated a deeper transformation of the Costa Rican political system.

The election saw a 69 percent voter turnout, the highest since 2010. This increase can be interpreted as a sign of civic revitalization, but also as a consequence of growing polarization. During the campaign, two distinct blocs emerged: on one side, the ruling party, organized around Chaves’s personalistic leadership; on the other, a fragmented opposition that, despite its ideological differences, shared concerns about the country’s institutional direction, and which ultimately consolidated most of its votes around the National Liberation Party. In the run up to the election, supporters of traditional and emerging parties came together. Concerned about the country’s democracy, they spontaneously organized various forms of collective action outside event venues. These activities culminated in the so-called “multicolored caravans,” named for the diversity of party flags displayed under the unifying slogan: “Out with Chaves!” But, despite such mobilizations, and in line with poll results, the opposition did not advance to a runoff.

From an organizational standpoint, the process was impeccable. The Supreme Electoral Tribunal once again demonstrated high standards of transparency and efficiency, reaffirming the technical soundness of the Costa Rican electoral system. However, this procedural strength contrasts sharply with the political tensions that accumulated during Chaves’s presidency, characterized by a confrontational discourse toward oversight bodies and the judiciary.

The Ruling Party and the Construction of Continuity

Fernández’s victory cannot be understood without considering the central role of the outgoing president. Although constitutionally barred from immediate reelection, Chaves devised a succession strategy based on personal loyalty and the symbolic transfer of his leadership. The official campaign revolved around the slogan “continuity of change,” presenting Fernández as the custodian of the president’s political mandate and as its guarantor of continued power.

The electoral vehicle was the Sovereign People’s Party (PPSO), created after Chaves fell out with the leadership of the Social Democratic Progress Party, with which he rose to power in 2022. The reorganization allowed it to concentrate the vote and achieve not only the presidency, but also 31 of the 57 legislative seats, an absolute majority unprecedented in recent decades.

This result substantially alters the conditions for governance. While previous administrations had to govern with small and fragmented factions, the new government will have a robust parliamentary group, although of late some friction has emerged among its leaders. Nevertheless, only the National Liberation Party – historically the most dominant political force in Costa Rica – had achieved a similar number of representatives in 1982, during an exceptional economic crisis.

This legislative majority opens the door to the possibility of far-reaching political reforms. During his presidency, Chaves repeatedly expressed interest in expanding the executive branch’s powers, limiting oversight bodies’ authority, and promoting a transformation of the state that his supporters call the “Third Republic,” a successive step in the destruction of the Second Republic inherited after the 1948 Civil War, whose foundations were laid by the liberationist José Figueres Ferrer. Without a supermajority, such reforms were not feasible. Today, the balance of power looks different.

During the transition period, two unprecedented decisions were announced. First, the president-elect expressed her intention to appoint Rodrigo Chaves as Minister of the Presidency, the sole responsible for coordinating actions between the executive and legislative branches. Second, the outgoing president appointed Laura Fernández as Minister of the Presidency for the remaining months of the administration. Chaves also stated that, in his future role, he would seek to bring on board members of the National Liberation Party to form the supermajority necessary to approve constitutional reforms.

Populism, Leadership, and Institutional Tensions

Rodrigo Chaves’s governing style represented a break with traditional Costa Rican political patterns. His confrontational rhetoric, directed against media outlets, public universities, judges, and opposition members of parliament, reinforced an anti-establishment narrative that resonated with sectors disillusioned with the status quo. His rhetoric fits into the political model followed by other populist presidents on the continent.

Surveys conducted by the Center for Political Research and Studies (CIEP) at the University of Costa Rica showed that his supporters primarily valued his ability to “impose order” and “produce results.” These attributes reflect a social demand for strong leadership and swift decisions, even if such an approach creates tension with the deliberative procedures inherent in liberal democracy.

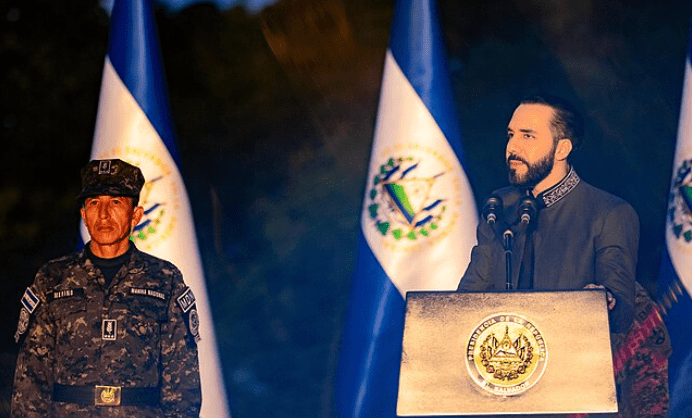

In this sense, the Costa Rican case fits into a broader regional trend. The political and inspirational affinity with Salvadorian President Nayib Bukele’s influence was evident throughout the campaign, particularly regarding public safety and proposals to toughen the prison system. Likewise, the first congratulatory messages to Fernández came from far-right figures such as Chilean president-elect Antonio Kast, and Mexican media figure Eduardo Verástegui, suggesting the integration of Costa Rica’s new leadership into transnational conservative-right networks. This realignment does not necessarily imply a break with traditional partners, but it does signal an ideological shift that redefines the country’s international standing.

Security, Social Cohesion, and a Democratic Future

The new government’s main challenge will be public security. The sustained increase in homicides and expansion of organized crime have eroded Costa Rica’s reputation as a peaceful exception in Central America. Policies implemented so far have been lax and ineffective, to the point that candidates labeled them permissive during the campaign debates.

Added to this are structural problems: the deterioration of the education system, the strain on the healthcare system, and the weakening of environmental policies that historically formed part of a national consensus. These issues not only affect social well-being but also undermine the legitimacy of a democratic system seemingly unable to improve the situation.

The 2026 elections do not simply represent a change or continuity of political parties. They reflect a reconfiguration of the political system around a personalistic leadership that combines right-wing populism, social conservatism, an evangelical agenda, and challenges to institutional checks and balances. The electoral strength of the ruling party is undeniable; so too is the broad-based support it received.

The underlying concern is undoubtedly that the new continuity government could further the trajectory of democratic erosion. When anti-institutional rhetoric is legitimized by those in power and the political concentration of that power is presented as a condition for effective governance, the risk is not an abrupt collapse but rather an incremental erosion.

For a society with a long tradition of stability and the rule of law, the central challenge will be to rebuild a minimal consensus around respect for horizontal checks and balances and pluralistic deliberation. The continuity of Chaves’s political project opens a new cycle. Its outcome will depend not only on the Executive and its legislative majority, but also on the capacity of the citizenry and institutions to maintain the balances that have historically defined Costa Rican democracy.