By Fábio Kerche*

Rodrigo Maia (center), Speaker of the House of Representatives, gives an interview to the Brazilian press. If President Temer loses the House, Maia may replace him as President.

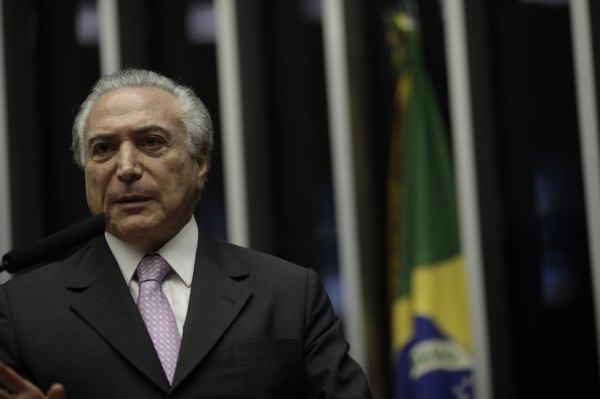

The political situation in Brazil is dramatic and shows no prospect of improving in the short term. The Supreme Court has received an indictment against President Michel Temer on corruption charges. A close adviser of his was caught on video receiving money in a suitcase. The Chief Prosecutor, who had been playing a minor role in the anti-corruption Car Wash Operation, saw an opportunity to grab the limelight. Rede Globo, Brazil’s most powerful media group, made Temer’s fall from power seem likely in a matter of days.

- But Temer did not surrender. As Supreme Court action against a president must be authorized by the House of Representatives, the battle turned to Parliament. Using means denounced as unethical, such as giving administration positions to people appointed by congressmen, the President won the first round in the committee with jurisdiction over the case. The next step, in August, will be a full House vote, which could reverse the committee decision.

Regardless of the outcome of House proceedings, political turmoil appears certain to continue – and Temer’s conservative policies will continue to aggravate social divisions. If Temer loses and the House gives a green light to a Supreme Court investigation, the Constitution foresees that he must be removed from the presidency during the trial (for up to 180 days) – with little chance of regaining the post, according to analysts. In this scenario, his most likely successor would be Rodrigo Maia, Speaker of the House of Representatives, and a member of a small right-wing party that supported the military dictatorship. He has little experience in electoral terms; many attribute his victories in legislative elections to the reputation of his father, a former mayor of Rio de Janeiro. His attempt to run for the executive branch in Rio de Janeiro, a more difficult kind of election than for the Congress, proved to be a huge failure. He is signaling that he would keep Temer’s conservative economic team and continue an agenda that cuts workers’ rights – proposals that are music to the market’s ears but likely to further rile opponents.

- An alternative pushed by social movements – a constitutional amendment calling for direct elections right now – would seem to offer a chance for Brazil to break its downward spiral. Protesters show little sign, however, of breaking the roadblocks that the mainstream press has created against the proposal. The popular mobilizations involve thousands of people but are having little resonance on television, in newspapers, and on websites. The government, press, and market do not wish to delegate to citizens the right to choose their president, at least not now.

By default, general elections scheduled for October 2018 still appear to be the country’s best hope for putting democracy on track again. The chance that the elections will end the crisis will be undermined, however, if former President Lula da Silva is barred from running. Convicted of corruption in a process that many observers claim lacked evidence, the matter is now in the court’s hands. If the conviction is confirmed, the legitimacy of the elections will be in jeopardy. Brazil’s political institutions will be further weakened as confidence in election results will plummet –more than in a healthy democracy – and the democratic game itself, as expression of popular rights and will, will be threatened. There is no hope of improvement in the short term. The impeachment without a crime of former President Dilma Rousseff continues to take its toll.

July 31, 2017

* Fábio Kerche is a Researcher at Casa de Rui Barbosa Foundation, Rio de Janeiro, and was a CLALS Research Fellow in 2016-2017.