By Marcio Cunha Filho*

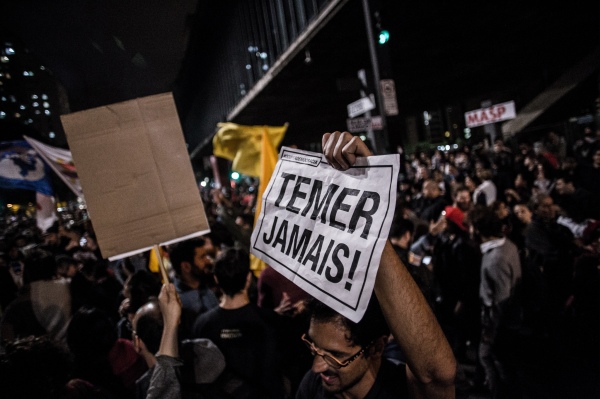

Demonstrators in São Paulo demanded the resignation of Brazilian President Temer on May 17, 2017. / Mídia NINJA / Flickr / Creative Commons

Brazil’s political turmoil has reached new heights with the leaking of audio recordings of President Temer allegedly authorizing bribes to prevent the former Speaker of the House, Eduardo Cunha, from concluding a plea bargain arrangement with investigators. Although the recordings were inconclusive and Temer alleges that they were fabricated, their emergence was enough to push an already fragile government to the verge of collapse in less than 24 hours. The day after the leak, according to press reports, four of Temer’s ministers were already discussing his replacement at a closed meeting with current Speaker of the House Rodrigo Maia, who is the next in line for succession. Some parties, such as the PPS, have already left Temer’s coalition. The PSDB, Brazil’s largest center-right party and Temer’s main coalition partner, is also discussing a possible withdrawal from government. (The party’s former President and one of Temer’s closest allies, Senator Aécio Neves, was removed from office by a Supreme Court decision as part of Operation Car Wash. (See here and here for previous articles about the Lava Jato investigations.)

- Temer has denied the possibility of resigning, but there are a few ways he could be forcefully removed from office. Most observers argue that, however he departs, the Constitution would require his successor to be indirectly elected by Congress within 30 days. Others posit, however, that if the Superior Electoral Court condemns Dilma and Temer together for illicit funding in the 2014 Presidential campaign – the trial is in early June and is likely to be the fastest possible way to remove Temer – then the electoral code dictates that new direct popular elections be held (as long as annulment is not declared within the last six months of their term, which ends in December 2018).

- Key political actors seem to be favoring the scenario in which Congress indirectly elects the successor. Although very fragmented, the Brazilian Congress is mostly conservative or right-leaning, and many of its members fear that former President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, who polls currently indicate would easily defeat any other candidate, might be elected in a popular election.

In this context, indirect election would put Brazil’s political system on the very edge of legality. During a similar crisis in 1964, Congress’s ousted left-wing acting Vice President João Goulart and elected another itself, without popular approval, in an act almost universally seen today as illegal. That act ended up throwing Brazil into a violent military dictatorship that lasted for more than two decades. In the current political crisis, if Congress were to act against the current rules of the electoral code and without popular approval, this could again be another step towards the establishment of an illegal regime, which could further curtail accountability and democratic mechanisms in the country. Placing the destiny of the country in the hands of a Congress, with many of its members under investigation themselves, might be a mistake with profound consequences. Popular elections would also entail great uncertainty as well, but the uncertainty of elections is an inherent element of democratic systems. When political actors try to limit or manipulate electoral outcomes in the name of predictability or security, this is when democracy dies.

May 19, 2017

* Marcio Cunha Filho is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Brasília; federal auditor in Brazil’s Office of the Comptroller General; and CLALS Research Fellow.