By Aaron Bell

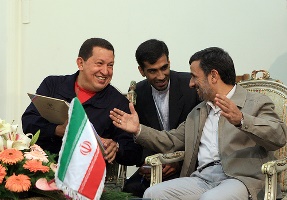

Former Presidents Hugo Chavez and Mahmud Ahmadinejad / Photo credit: chavezcandanga / Foter.com / CC BY-NC-SA

During his campaign for the U.S. presidency, Republican Mitt Romney referred to Russia as the United States’ number one geopolitical foe, but in the Latin American context he and his fellow conservatives have focused much more on another perceived competitor – Iran. Alongside China and the EU, Russia has indeed taken greater interest in Latin America in the past decade, investing in energy, selling military hardware, and even offering an alternative to Washington’s counternarcotics programs. But Romney and major elements of his party have given more attention to the newer, more enigmatic go-to threat of Iran and its former president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The 2012 Republican Party Platform warned that Venezuela had become “an Iranian outpost in the Western Hemisphere,” issuing visas to “thousands of Middle East terrorists” and providing a safe haven to “Hezbollah trainers, operatives, recruiters, and fundraisers.” This past spring, former Assistant Secretary of State Roger Noriega told a Congressional committee that Hezbollah was working alongside the Sinaloa Cartel to fund and organize terrorist activities. He claimed the organization had infiltrated the Venezuelan government so the Iranian government could launder money through Venezuelan banks to avoid international sanctions.

Relations between Iran and some members of ALBA expanded during Ahmadinejad’s presidency, during which he spent more time in Latin America than either Presidents Bush or Obama. He shared the stage with Hugo Chávez and Daniel Ortega in denouncing the United States and its policies toward both Iran and the ALBA nations, and he pledged to invest in Venezuela, Bolivia, and other countries. The warmth of that contact gave credibility to rumors that Iran has used elite Quds soldiers and Hezbollah agents to create a web of Latin American agents available for terrorist strikes in the United States. As required by the Republican-sponsored “Countering Iran in the Western Hemisphere Act,” the State Department released a report this summer analyzing Iran’s regional activities. While it expressed concern over Iran’s political and economic links, it concluded that Tehran’s regional commitments had largely gone unfulfilled. Nonetheless, a handful of U.S. Congressmen and the media continue to warn of the looming Iranian threat along what conservative commentators call the “‘soft belly’ of the southern border.”

The Obama Administration has not dismissed entirely the negative impact that a country like Iran can have in Latin America, if nothing else by encouraging political leaders to sustain their anti-U.S. rhetoric campaigns. But the Administration has not subscribed to the right wing’s exaggerations about Iranian activity and indeed is seeking pragmatic agreements with Iran to resolve a series of concerns about its activities, particularly its nuclear program. A handful of members of Congress led by Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen (R-FL), former Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, have accused the Obama administration of putting politics over national security by failing to challenge Venezuela and other Iranian allies, though the political advantage the president supposedly achieves with such a policy is unclear. Some xenophobic nationalists on cable TV believe the Iranian activities are part of Islamic imperialism, which poses a threat to Western civilization. Others see the threat as being embodied by Barack Hussein Obama, accusing the administration of hyping the Iranian issue as a pretext to justify the expansion of a U.S. military presence in South America. Today’s paranoia about Latin America is different from during the Cold War years, but only in the identity of the villain. Latin America’s role in the new narrative remains unchanged: it exists primarily as a base of operations for foreign enemies of the United States that must be monitored and pressured to ensure U.S. national security. While the rhetoric of ALBA leaders and their efforts to establish friendly relations with regimes like Iran fuel such paranoia, Washington would be wise to respond to actions rather than empty rhetoric. Fortunately, the Obama administration appears to be doing just that.