By Sonja Wolf

Research Professor, School of Government and Economics, Panamerican University, Mexico

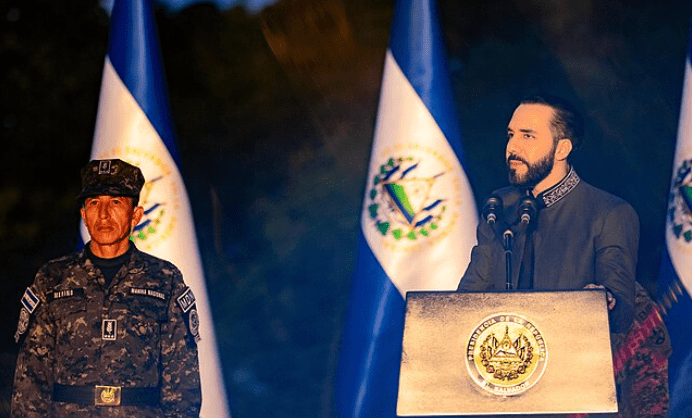

Nayib Bukele on Salvadoran Independence Day in 2024. (Source: Wikimedia)

On December 17, 2025, a local court released lawyer Alejandro Henríquez and pastor José Ángel Pérez. Seven months earlier, the two activists had been arbitrarily detained under El Salvador’s state of emergency and charged with public disorder and aggressive resistance. The arrests occurred when Henríquez and Pérez were attending a peaceful rally of the El Bosque cooperative outside President Nayib Bukele’s private residence. The El Bosque cooperative is a farming community that had obtained its lands because of agrarian reforms in the 1980s and was now making a last-ditch effort to prevent the eviction of more than 300 families from their plots. In a bittersweet turn of events, Henríquez and Pérez pled guilty to regain their freedom after an abbreviated judicial process. Each received a suspended three-year prison sentence that essentially prohibits them from participating in protests during this time. The verdict criminalizes social movement activity and is a reminder that the state of emergency has become a tool to silence critical voices.

Generalized citizen discontent with the country’s traditional parties and his own anti-establishment campaign had propelled Bukele to the presidency of El Salvador in 2019. Since then, he has quickly established an electoral authoritarian regime that retains a democratic façade but sees him wield executive control over other branches of government. His party, Nuevas Ideas, obtained a legislative supermajority in both the 2021 and 2024 elections. Bukele capitalized on these wins to neutralize all checks and balances on his power and to engineer his successful run for an unconstitutional second mandate in 2024. A secret pact with the country’s street gangs helped mobilize voters and contributed to Bukele’s early triumphs at the ballot box. In late March 2022, the breakdown of this agreement prompted gang members to kill 87 people in three days. By then, Bukele no longer needed the gangs to consolidate his rule.

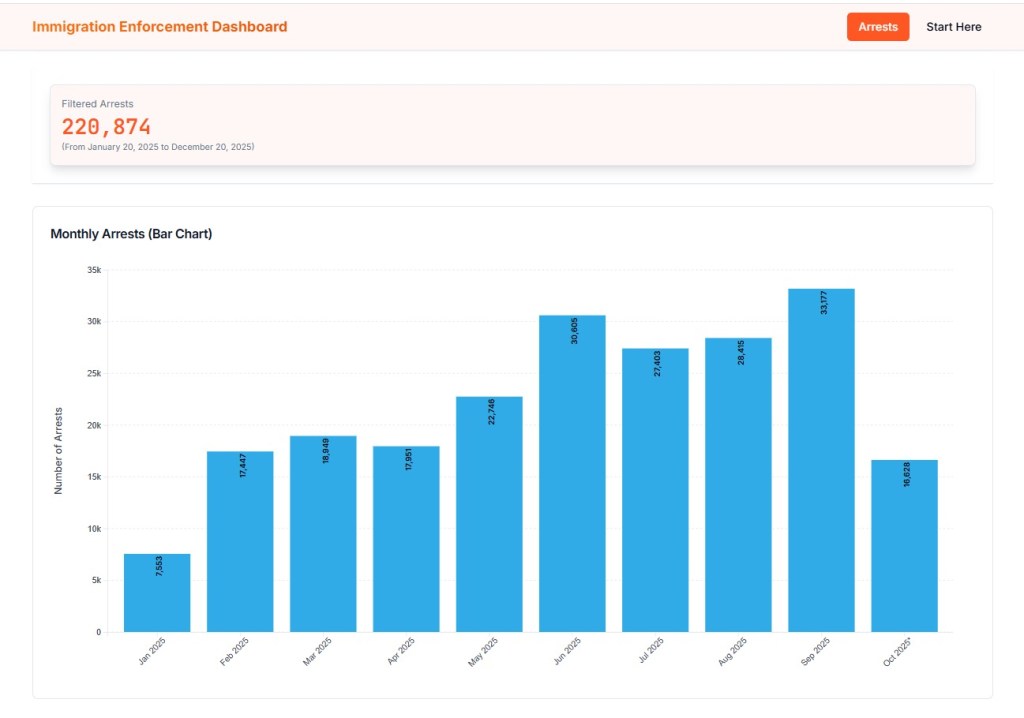

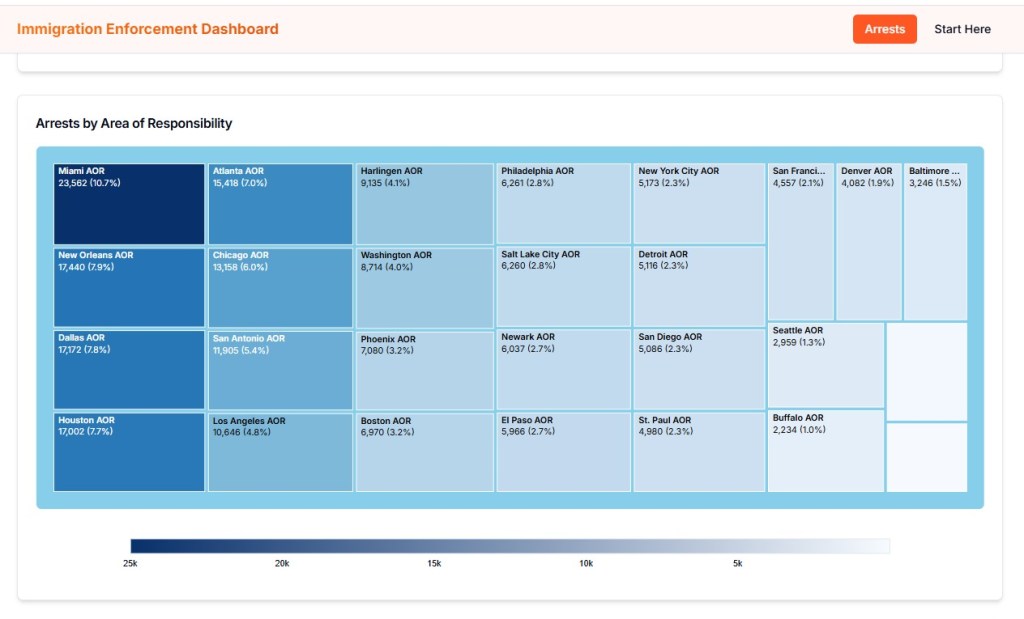

Following this latest escalation in violence, he asked the Legislative Assembly to declare a state of emergency to crack down on these groups. The measure, which suspends certain constitutional rights and allows extended pretrial detention, dismantled the gangs as the country knew them and sharply cut the number of registered homicides. While the administration appears to be manipulating crime statistics, its perceived results made the state of emergency widely popular with Salvadorans and helped Bukele’s re-election in 2024. Far from being of a temporary nature, the measure has come to fulfill an essential function in the regime’s propaganda and repression. Some 90,000 people have thus far been detained, including human rights defenders and political opponents. Often apprehended on the spurious charge of illicit association, individuals find themselves mired in a justice system that does not ensure a fair trial. Civil society groups have extensively documented the systematic human rights violations committed under the state of emergency. The abuses are particularly egregious in the prisons where, by December 2025, they had occasioned at least 473 deaths.

The weaponization of the state of emergency follows the progressive closure of El Salvador’s civic space. Bukele’s regime has severely restricted access to public information, making it difficult for reporters and transparency activists to obtain data about government policies, contracts, spending, and statistics. If anything, this opacity has increased under the state of emergency. Since he came to power, Bukele has denied independent journalists access to press briefings and subjected them to systematic campaigns of stigmatization and delegitimization. Efforts aimed at undermining critical media workers range from online harassment and defamation to surveillance and abusive legal tactics such as Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation or SLAPPs, initiated to exhaust targets financially and emotionally.

At El Faro, an award-winning investigative outlet, journalists received physical threats and Pegasus spyware attacks. Advertisers were harassed, and the newspaper faced spurious money laundering accusations and frivolous audits. Jorge Beltrán is a veteran reporter who had been covering organized crime and gangs for El Diario de Hoy, one of El Salvador’s oldest mainstream newspapers. In 2022 Beltrán was targeted with a $10 million SLAPP after an exposé about Israeli cyber espionage firms in Mexico. A relative of the director of El Salvador’s state intelligence agency was mentioned in the piece and subsequently sued both the newspaper and Beltrán for moral damage. While the court rejected the compensation claim, it required El Diario de Hoy to publish an apology and withdraw the article. Beltrán himself went into exile in June 2025 because of a reasonable fear of being arrested on fabricated criminal charges.

For Salvadoran civil society, however, it was the arbitrary detention of Ruth López that constituted a watershed moment. As lead anti-corruption investigator for Cristosal, a prominent human rights NGO, López had worked on cases of government corruption and irregularities in public contracts involving Bukele’s relatives. Her arrest in May 2025 on spurious grounds of illicit enrichment had a chilling effect. Since 2020, at least 130 journalists and human rights defenders have gone into exile, though most of them left El Salvador in the aftermath of López’s capture to avoid meeting a similar fate. In addition to individual departures, NGOs and independent media organizations also felt compelled to exit the country. El Faro had already moved its legal office to Costa Rica in 2023, whereas Focos and the Journalists’ Association of El Salvador (APES) did so two years later. As government repression increased throughout 2025, El Faro and Cristosal moved all of their staff abroad for their own safety. The decision to reduce the organizations’ in-country presence, while understandable, will pose new challenges to documenting abuses of power, defending its victims, and holding officials accountable.

Bukele’s regime found an additional mechanism to quash dissent with the Foreign Agents’ Law passed in May 2025. The legislation requires non-profits to register with the interior ministry and pay a 30 percent tax on all foreign funding they receive. The decree gives the administration broad powers to monitor, sanction, and dissolve organizations that fail to register or that engage in political activities that threaten the stability of the country. In response, some NGOs voluntarily decided to close, many others try to keep operating with a low profile. The Jesuit Central American University, long a vocal advocate for the poor and oppressed, is known in El Salvador for its research, public opinion surveys, and human rights reports. Its leadership, however, must now hope to avoid a repeat of what happened in Nicaragua where the Ortega regime seized the school’s property and assets in 2023. In El Salvador, meanwhile, proposed reforms to the rules governing communal associations suggest a government intent upon hindering community organizing. For anyone working in NGOs, media, and academia, self-censorship becomes a survival strategy. As journalist Raymundo Riva Palacio remarked, regarding the erosion of press freedom in his native Mexico, self-censorship is the most effective form of censorship, because it leaves no trace, creates no scandal, and normalizes silence.

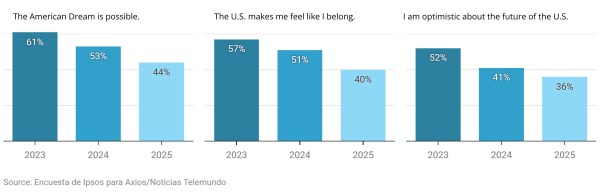

Self-imposed exile and self-censorship are turning El Salvador into what the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights has called a “zone of silence.” The term is typically associated with areas where violence against journalists leaves entire communities misinformed, as has happened in Mexico. A similar trend is occurring in El Salvador since the Bukele administration is deploying “technologies of censorship” to inhibit public scrutiny and criticism. The resultant information vacuum is filled by the official narrative, extensively promoted through government-controlled television channels, newspapers, and social media accounts. Influencers and pro-Bukele trolls do their part to spread regime propaganda and attack human rights defenders, journalists, and opposition politicians. Since citizens primarily rely on television and social media to access information, Salvadorans are likely relatively unaware of major government decisions and their impacts on people’s lives.

Exiles may have escaped state terror at home. Some stay out of the public eye to keep their relatives in El Salvador out of harm’s way. Others continue their professional work as best as they can, but they have started to be impacted by Bukele’s methods of transnational repression. The United Nations Human Rights Office defines transnational repression as acts that a state or its proxy commits to deter or punish advocacy directed towards it from abroad. It can take various forms, including digital attacks, reprisals against in-country relatives, the arbitrary refusal of consular services, harassment through INTERPOL red notices, and physical violence. Ingrid Escobar directs Socorro Jurídico Humanitario, a legal aid organization that assists victims of the state of emergency, and has repeatedly been subjected to online defamation campaigns. Ivania Cruz and Rudy Joya of the human rights organization UNIDEHC were targeted with INTERPOL red notices but managed to have these lifted.

Given the Bukele regime’s persistent attempts to intimidate journalists and activists, it is vital that these groups create international pressure to denounce abuses and demand respect for human rights. It is equally important that exiles find spaces for collective solidarity and resistance. Their ability to continue their work is key, more so since parts of the international community are either reluctant to criticize the democratically elected Bukele or perceive his security “model” as effective. APES documents and reports abuses against journalists and offers media workers safety guides and legal assistance. In Mexico City, Casa Centroamérica has become a home for Central Americans fleeing political and legal persecution. The NGO can provide recent arrivals with temporary shelter, is building an archive of national publications, and researches the causes of exile.

Realistically, the state of emergency only stands a chance of being dismantled if El Salvador returns to democracy. Many citizens choose not to report abuses or speak out against Bukele’s regime for fear of being arbitrarily detained. Constitutional reforms passed in July 2025 extend the presidential term to six years, permit indefinite re-election, abolish the runoff election, and brought the next presidential election forward to 2027. Bukele can comfortably perpetuate himself in power if abstention levels are high and the political opposition fails to present a compelling alternative to his vision of the country. During Bukele’s time in government, economic growth has been weak, and poverty has increased as soaring debt and corruption have depleted state resources. A fiscal adjustment insisted upon by the International Monetary Fund requiring a smaller public sector has already led to massive job losses in areas such as health and education. These cuts will affect the quality of public services and likely fuel social discontent. The country’s economic woes, which Bukele will be unable to resolve as quickly as the security situation, may ultimately help bring about the demise of his regime.