By Sophia Robinson

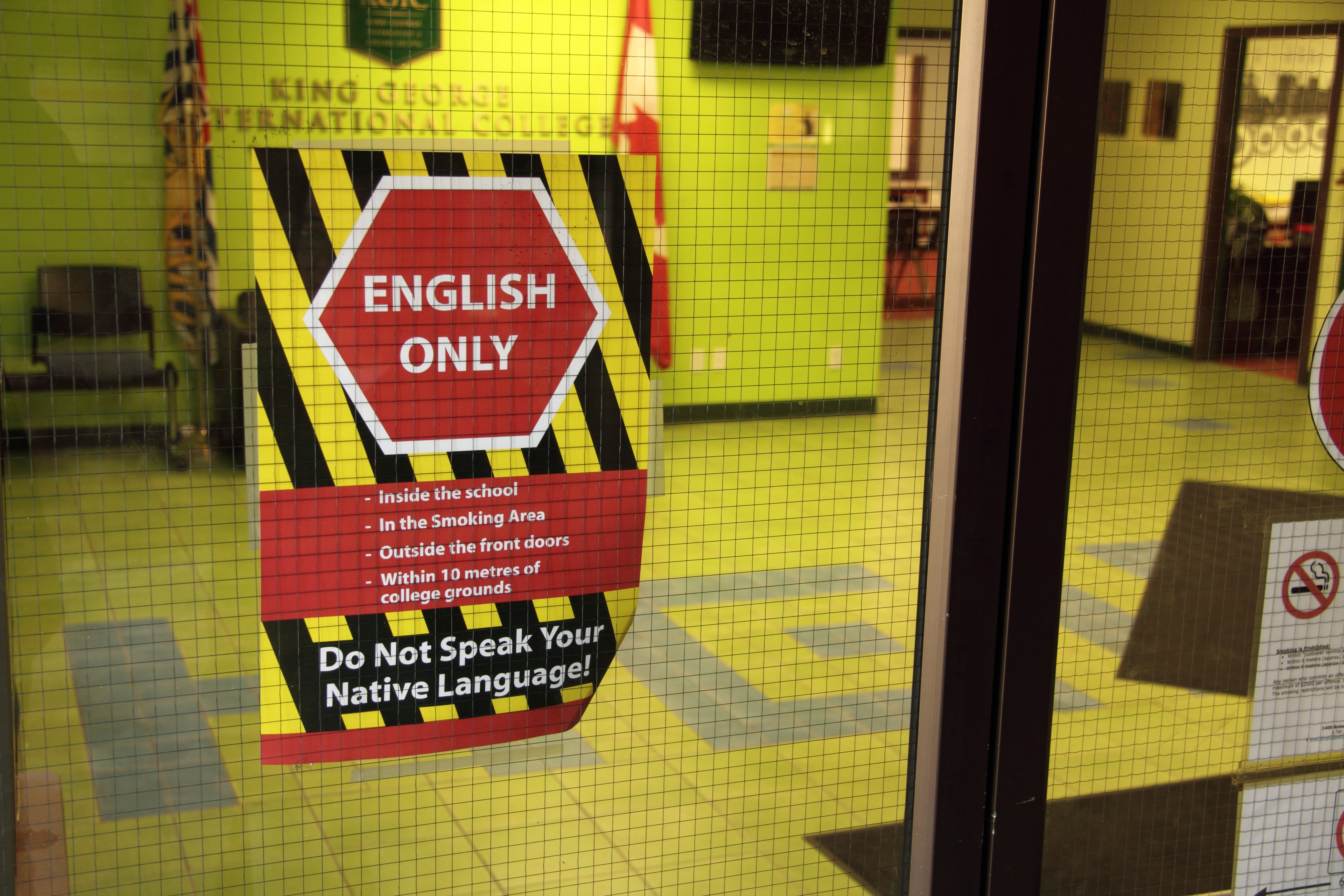

Stop sign “English Only”. Image from flicker

On March 1st, 2025, President Trump passed Executive Order 14224 making English the official language of the United States; this decision will undoubtedly have profound societal effects, further marginalizing migrant communities and diminishing multiculturalism in the U.S. By examining this order alongside a summary of “Immigrants Want to, and Do, Learn the Local Language,” Chapter Four of Immigration Realities: Challenging Common Misconceptions by Ernesto Castañeda and Carina Cione, it is possible to see how this action will affect the lives of millions across the U.S.

This Executive Order revokes President Clinton’s 2000 policy requiring language assistance for non-English speakers. Executive Order 13166 (“Improving Access to Services for Persons with Limited English Proficiency”) helped non-native speakers access essential services, including government documents, healthcare forms, and voting materials, and its absence could leave millions without access to these vital resources. The dynamics of language barriers are rooted in both historical and contemporary struggles faced by immigrants in the U.S, and Clinton’s 2000 policy was designed to ensure that non-English speakers could access government services without facing language-based discrimination. Trump’s order frames English as central to a cohesive American identity, which is inherently multifaceted and complex.

Supporters of this recent order argue that designating one language will improve the efficiency of government operations and promote national unity. However, this change can have serious consequences, especially for immigrant communities who rely on translated government materials for essential services. With over 68 million U.S. residents speaking a language other than English at home, Executive Order 14224 threatens to further marginalize a significant portion of the population both through limited required accessibility to government services and further reinforcement of misconceptions about migrants’ desire and ability to learn English.

As Castañeda and Cione’s book highlights, the challenges non-English speakers are far more complex than they appear. Many immigrants, especially those from Latin America, face significant social, economic, and legal barriers to learning English. Even with sufficient economic means, access to language education varies by region and available free time. Discrimination adds another layer of difficulty, with nearly half of Hispanic immigrants feeling judged for their English abilities. As a result of various obstacles, many are left isolated and unable to fully integrate into American society. A policy that systematically and socially upholds English as the only possible standard for success will only worsen these challenges.

Language assimilation is further complicated when considering the gendered challenges of language learning. Immigrant women, particularly in Latino communities, often face more difficulty learning English due to domestic pressures, cultural expectations, and fears of discrimination. This reinforces cycles of economic and social marginalization, as women are often left without the tools to access better opportunities.

Language barriers can have serious consequences for mental and physical health, leading to stress, isolation, and even misdiagnosis in healthcare settings. It is vital to uphold and validate the multicultural realities of the U.S. in all spaces and having that upheld in government accessibility is a crucial part of inclusion. Lack of support for bilingualism and multicultural identity can lead second and third generation migrants to lose contact with their linguistic and cultural heritage, which has proven to be harmful to community health and well-being. The executive order’s reduction of language assistance programs will only worsen disparities and perpetuate negative perceptions of multilingualism in the U.S.

The implications of Executive Order 14224 are clear: it risks exacerbating the social and economic divides between English-speaking citizens and immigrants. While the goal of national unity is important, the needs of non-English speakers should not be overlooked. If the federal government reduces its support for language assistance, vulnerable immigrant populations will face even greater challenges in accessing essential services, deepening existing inequalities. Policymakers must consider the long-term impact of such decisions on social cohesion and the well-being of all citizens, regardless of language and background.

Sophia Robinson is a Research Assistant at the Center for Latin American & Latino Studies at American University