Ernesto Castañeda

Entrevista de Diana Castrillón a Ernesto Castañeda publicada por Stornia 13 de agosto de 2024 editada y expandida por Castañeda.

Diana Castrillón: “La inmigración irregular es uno de los temas más importantes de las campañas presidenciales de los candidatos, el republicano Donald Trump y la demócrata Kamala Harris. Por un lado, la administración de Biden-Harris restringió el número de solicitantes de asilo que pueden ingresar al país. Por otro lado, los republicanos están prometiendo el “mayor programa de deportación masiva en la historia de Estados Unidos” si es que ganan la Casa Blanca este otoño.

El sentimiento antiinmigrante en Estados Unidos está en aumento. Este año, el 55% de los estadounidenses dijeron que les gustaría ver una disminución de la inmigración, una novedad desde el 2001. Esto se debe en parte a la creencia que los inmigrantes, en particular los indocumentados, son una carga para los recursos del gobierno y no contribuyen en nada.

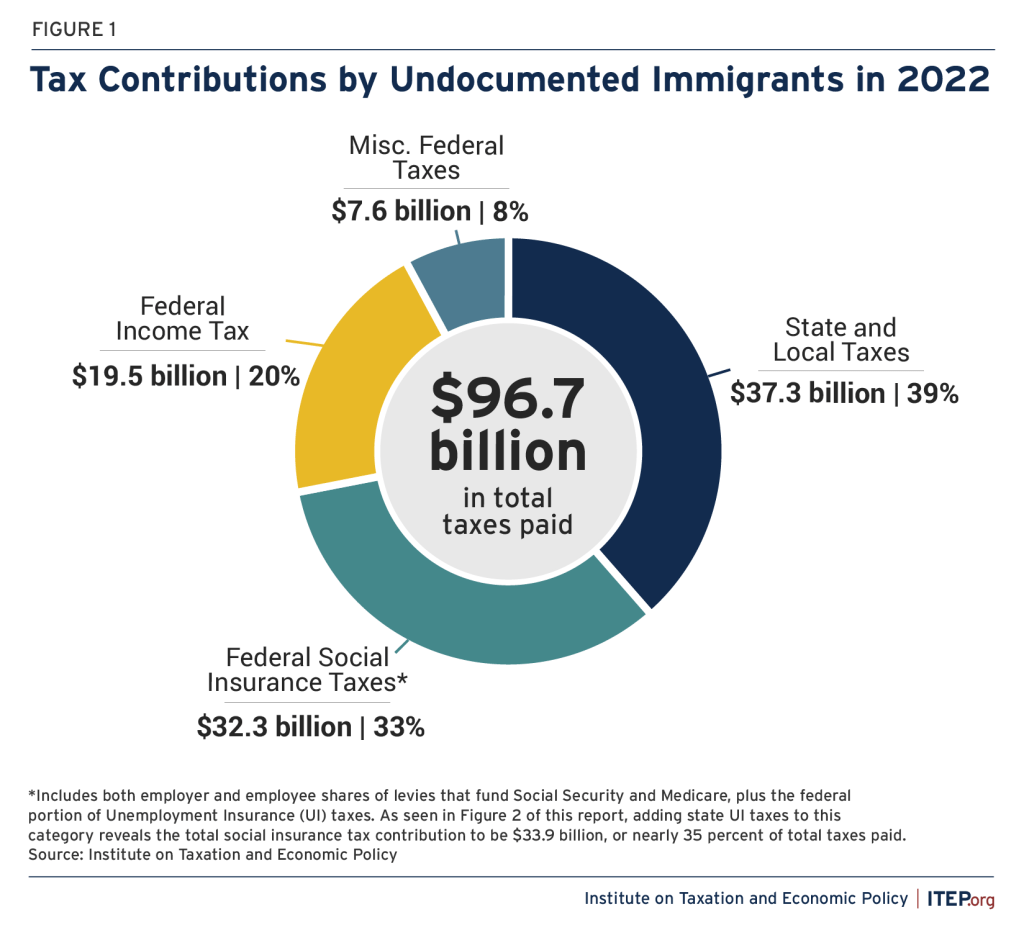

Sin embargo, un nuevo estudio del Instituto de Política Fiscal y Económica muestra que es todo lo contrario. Según el informe, los inmigrantes indocumentados contribuyeron con casi $100 mil millones de dólares en impuestos durante 2022 y a su vez, no pudieron acceder a muchos de los programas que financiaron sus dólares de impuestos.

De esos casi $100 mil millones, $60 mil millones se destinaron al gobierno federal. Por cada millón de inmigrantes indocumentados, los servicios federales reciben $8.900 millones de dólares adicionales en ingresos fiscales. Más de un tercio de los impuestos que pagan estos inmigrantes se destinan a programas a los que no pueden acceder, como la Seguridad Social ($25,700 millones de dólares), salud Medicare ($6,400 millones de dólares) y el seguro de desempleo ($1,800 millones de dólares).

Los indocumentados suelen pagar tasas impositivas más altas que los ciudadanos estadounidenses. En 40 de los 50 estados del país, los inmigrantes irregulares pagan tasas de impuestos estatales y locales más altos que el 1% de los hogares con mayores ingresos. Además, no pueden recibir muchos créditos fiscales. No se dan cuenta que pueden reclamar reembolsos y tampoco tienen acceso a ayuda fiscal.

“En total, la contribución fiscal federal de los inmigrantes indocumentados ascendió a $59,400 millones de dólares en 2022, mientras que la contribución fiscal estatal y local se situó en 37,300 millones de dólares”, escribieron los autores del estudio. “Estas cifras dejan claro que las decisiones sobre política migratoria tienen implicaciones sustanciales para los ingresos públicos en todos los niveles de gobierno”, menciona el informe.”

En entrevista con Stornia, Ernesto Castañeda PhD, Director del Laboratorio de la Inmigración y el Centro de Estudios Latino Americanos y Latinos de American University en Washington DC, aseguró que los inmigrantes son necesarios y esenciales para el crecimiento económico de Estados Unidos.

Diana Castrillón: ¿Cómo paga un inmigrante indocumentado impuestos, si como su nombre lo dice, son migrantes irregulares?

Ernesto Castañeda: Los indocumentados pagan impuestos cada vez que compran algo, está el impuesto a la compra, el porcentaje depende de cada localidad. Si compran casas, que lo pueden hacer, también pagan impuestos, si rentan o pagan renta, también hay un porcentaje que se debe pagar en impuestos al gobierno local y federal. La gente indocumentada que trabaja en compañías formales, que son muchos, pueden tener una identificación temporal para pagar impuestos (ITIN), que funciona de manera similar al número de Seguridad Social, entonces pagan impuestos a la nómina como cualquier otra persona trabajando en Estados Unidos. Hay gente que usa documentos de identidad falsos o que no les corresponden, pero alguien se los presta, y así pagan a las arcas de Seguro Social y programas de retiro y de salud, pero como el número es falso o no es de ellos, no tienen acceso a esos beneficios.

Entonces, no solo pagan a estos servicios, sino que muchos inmigrantes no piden ese apoyo. Por lo tanto, tienen una contribución mayor a los ciudadanos que pagan, pero quien luego si retiran esas ayudas. Es una ganancia que el Gobierno Federal y el Tesoro aceptan abiertamente que sucede.

¿Entonces los inmigrantes indocumentados están pagando más impuestos que los mismos ciudadanos americanos?

Si, la tasa de muchos indocumentados que pagan impuestos es más alta que las tasas que paga la gente más rica del país. Claro, los ingresos son diferentes pero la tasa es a veces mayor o muy similar, a la de los ciudadanos. Los ciudadanos llenan sus declaraciones de impuestos y muchas veces piden reembolsos, por ejemplo, por gastos de negocios o les dan un crédito por tener hijos, pero muchos de los indocumentados no hacen esos reclamos porque no quieren que más adelante se les niegue la ciudadanía por haber pedido ayudas o servicios. Por ese temor, tampoco piden programas de apoyo para sus hijos, que ya son ciudadanos y tienen derecho a esos servicios. Hemos comprobado en nuestras investigaciones en el Laboratorio de Inmigración que los inmigrantes usan menos servicios sociales que los nacionales (Castañeda y Cione, 2024).

Pareciera que los indocumentados están entre la espada y la pared ahora con la campaña electoral tanto por el lado de los republicanos como por el lado de los demócratas, ¿hay preocupación en la comunidad?

Algunos políticos usan a los inmigrantes indocumentados como chivos expiatorios en tiempos electorales. Por un lado, Trump hace esta amenaza de deportaciones masivas, pero es poco probable que lo haga, eso mismo lo había prometido anteriormente y cuando fue presidente no deportó a tanta gente. Eso no significa que la gente no tenga miedo ahora y si gana creará un terror real entre la población que ya de por sí vive con mucho miedo a que los encuentren como indocumentados a ellos o a alguien cercano.

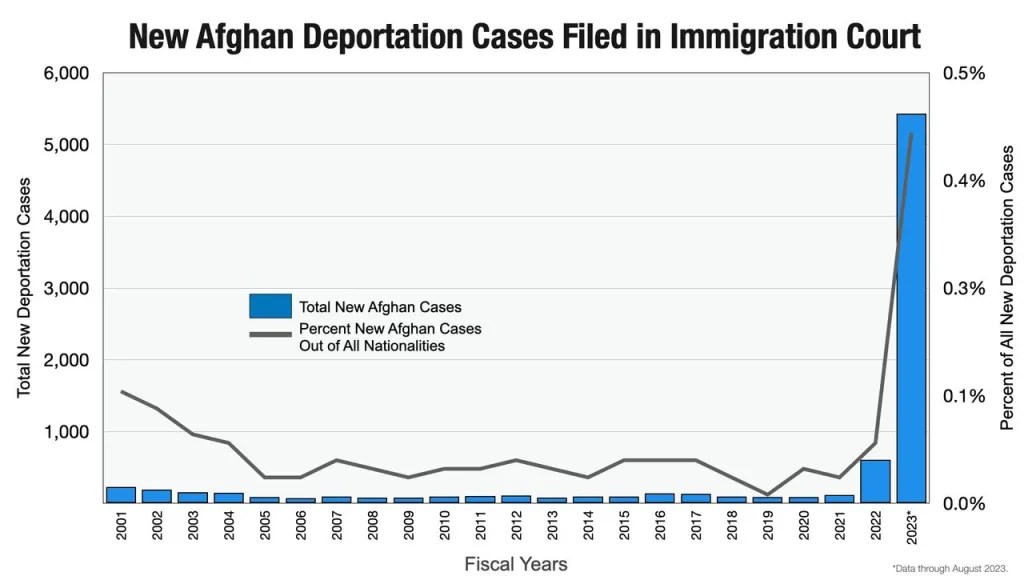

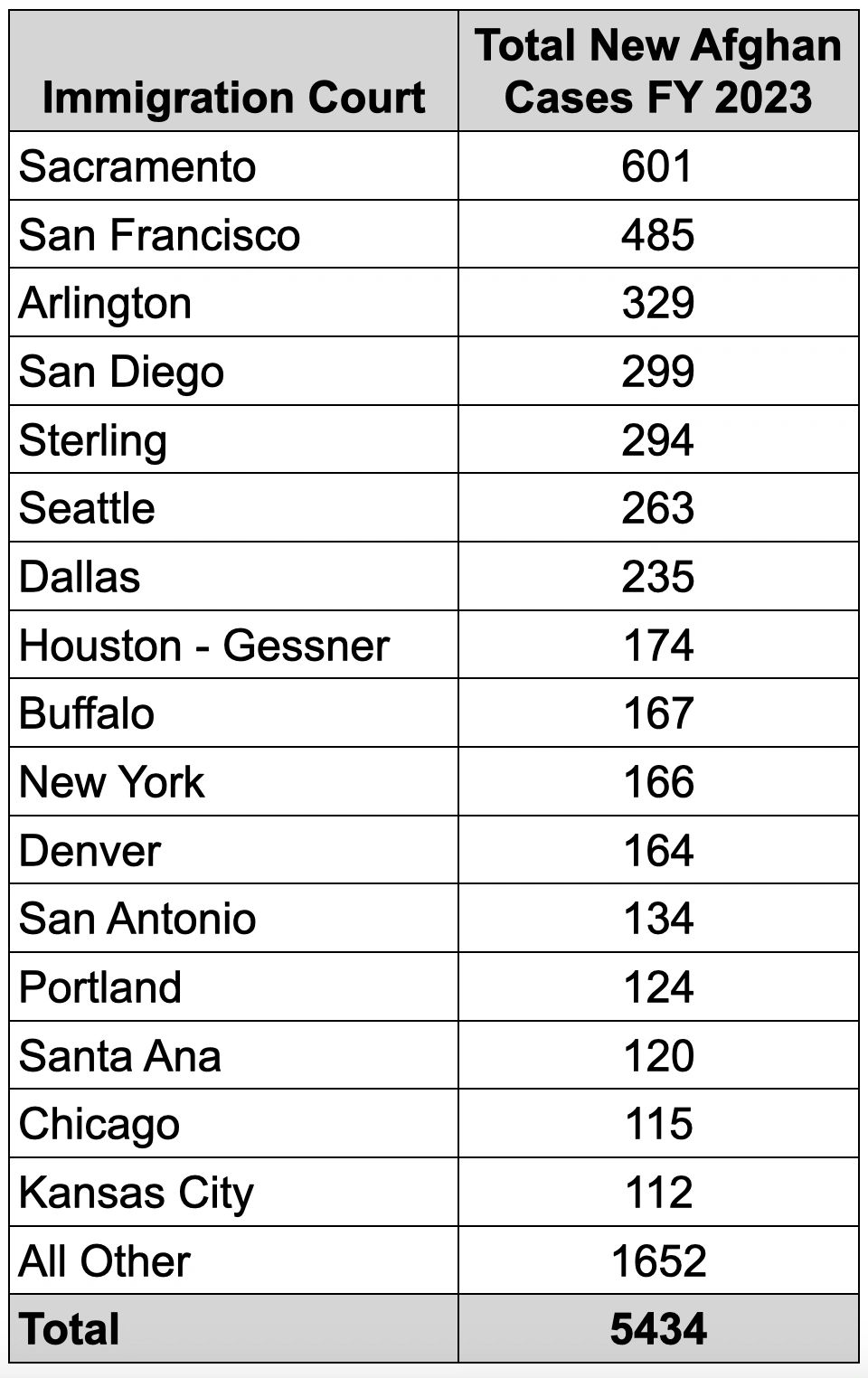

En cuanto situaciones de asilo, en efecto, mucha gente está escapando de situaciones difíciles en Afganistán, Ucrania, Cuba, Venezuela, Haití o Nicaragua. Muchos con pruebas de persecución, y ahora el gobierno ha cambiado cómo tramita buscar asilo. La frontera está cerrada a muchas de esas peticiones de asilo como se hizo durante la pandemia. Por ende, estamos viendo menos cruces irregulares en la frontera. La administración Biden-Harris piensa que eso les puedes ayudar electoralmente para que los republicanos no les hagan la crítica de que la frontera está supuestamente abierta y los que indocumentados o quienes piden asilo están recibiendo comida y vivienda en algunas ciudades. Es un momento difícil, y no es sostenible. En algún momento van a tener que reabrir la frontera al asilo humanitario, porque a lo que llaman el derecho nacional e internacional es a recibir a la gente que está pidiendo asilo. Tras procesar sus aplicaciones, a unos los aceptarán a otros no.

Trump necesitaría mucho dinero y mucha policía, casi tendría que crear un estado totalitario para poder deportar a toda la gente que está aquí sin papeles migratorios en regla. Muchas de estas personas tienen más de 10 años aquí, tienen hijos ciudadanos, trabajan, contribuyen, por lo cual, deportar masivamente o dejar de recibir inmigrantes es un gran ataque a Estados Unidos. La economía se podría contraer. Se podría crear una recesión porque como mencionamos anteriormente, los migrantes pagan miles de millones en impuestos, pero los impuestos son un porcentaje pequeño de lo que la gente gana. La mayoría de los inmigrantes ganan, lo gastan en las ciudades donde viven, y con el trabajo que hacen generan crecimiento económico, servicios, entretenimiento y hacen que la economía crezca.

Hace algunos días JD Vance, la fórmula vicepresidencial de Donald Trump justificaba el plan de deportación masiva y decía que los indocumentados le están robando plazas de trabajo a los ciudadanos americanos. ¿Existe esa fila de estadounidenses esperando a que deporten inmigrantes para tomar sus puestos de trabajo?

Esto no funciona así. Trump y Vance están equivocados sobre que los inmigrantes les quitan trabajos a los afroamericanos o a otros ciudadanos. Es un estereotipo fácil de vender, algún votante pudo haber tenido una experiencia donde pareciera que pudo ser el caso, sin embargo, si vemos a la economía en general, la inmigración genera nuevos empleos.

En Florida, está en efecto la ley anti-inmigrante más estricta del país. De hecho, han salido muchos indocumentados del estado, y hoy no hay suficiente mano de obra para la construcción, para servicios como hoteles, para la agricultura en los cultivos de naranjas. Entonces los negocios que necesitaban esa mano de obra para generar riqueza ahora no pueden tener su negocio al 100%. Propietarios de granjas han tenido que cerrar porque les falta mano de obra para trabajar, algunos negocios pequeños han tenido que limitar sus horas de servicios. Si no hay construcción no hay viviendas, seguirá habiendo inflación por las viviendas existentes. Los inmigrantes llegan y necesitan un lugar donde vivir, quien les corte el pelo, quien les venda comida, entonces generan trabajo e ingreso para los comerciantes.

Los migrantes emprenden con más negocios (desde pequeños negocios hasta las grandes empresas) que los nacidos en Estados Unidos. También sabemos que los inmigrantes emplean más gente que los dueños de negocios del país. No es que haya un pastel que esté limitado y se lo reparta el número de gente que llega, entre más personas lleguen, incrementa el tamaño del pastel entonces hay más pastel para todos. No es una competencia desleal y eso se ve en las tasas de desempleo.

Ahora bajo la administración Biden-Harris tenemos una tasa de desempleo para afroamericanos históricamente baja, una tasa de desempleo de latinos muy baja y no hay muchos ciudadanos de origen europeo que están desempleados porque algún migrante esté tomando su trabajo, si noq que usualmente no encuentran trabajo porque no los estudios o capacitación suficiente para tomar un empleo bien pagado, o por el contrario, porque tienen demasiada educación y no hay un empleo con alto ingreso que les convenga tomar. O porque se rehúsan a mudarse dentro del país para buscar trabajo. Las tasas de desempleo son bajas en general y de lo que se quejan los empresarios es que no tienen suficiente personal para expandir sus negocios. Esto también afecta a los ciudadanos buscando servicios, teniendo que esperar más en restaurantes porque no hay suficientes meseros o cocineros.

¿Cuál es la respuesta para el manejo de inmigración, más visas temporales de empleos, legalizar a los indocumentados o hacer más muro en la frontera?

La solución a los casos de inmigración irregular a largo plazo es aumentar las visas temporales de empleo para que la gente venga de manera legal. Existen programas como la Visa H2A, H2B son ejemplos de visas que funciona muy bien, la gente viene, trabaja y se regresa a su país, porque ya ganaron ingresos en dólares pudieron ahorrar suficiente y ahora quieren estar con su familia.

El problema es que hay límites, hay cuotas para esas visas, son para cierto tipo de empleos, y hay más demanda de esa gente trabajadora temporal de lo que la que la ley permite. Para que aumenten los topes, los números de esas visas, el Congreso tiene que actuar. Tiene que actuar la Cámara de Representantes y el Senado, y tienen que estar de acuerdo los demócratas, de que es lo que harían, y un número suficiente de republicanos. Pero ellos se niegan a hacerlo, porque parece que no quieren solucionar el tema, solo lo quieren usar de manera electoral.

Para las personas que ya están aquí, la solución es legalizarlos. Al darle papeles o permisos laborales a quienes están aquí, de esa manera muchos ganarían más dinero, tendrían más confianza de invertir, pagarían más impuestos. Esto sería una inyección a la economía americana, y podrían traer a sus familiares de manera legal y expandir la base trabajadora un poco más.

Y eso es algo que ni Trump ni Vance entienden, nunca lo harán. A diferencia del presidente Ronald Reagan, quien sí firmó una ley como esa, aunque a regañadientes. Tampoco es algo sobre lo que han querido hablar mucho Kamala Harris ni Tim Walz en la campaña porque la gente lo usa como un ataque muy simple con ellos, pero los dos tienen un historial político de apoyar este tipo de medidas.

¿Y con esta legalización de indocumentados en Estados Unidos ganan países de América Latina o pierden?

Las remesas representan solo el 4% de lo que los inmigrantes generan en Estados Unidos. Un migrante que está más establecido o es profesional, manda remesas menos seguido, entonces son ayudas a familias en pobreza. Las remesas representan separaciones familiares por años hasta que el migrante termina regresando o trata de traer a la familia entera. Es una ayuda a corto plazo, pero pone a las familias que se dividen en dificultad emocional y cualquier país que pierde migrantes, desde agricultores hasta científicos, médicos, como en Cuba que ha perdido un par de millones de migrantes profesionales durante el último par de años debilita cada vez más su economía. También pasa en la economía venezolana, que ha sido debilitada entre otras muchas cosas por la emigración. Las remesas son ayudas de corto plazo, pero la verdadera ayuda económica se da en donde llegan los migrantes, en este caso Estados Unidos.

De acuerdo con el estudio de Instituto de Política Fiscal y Económica, la autorización de trabajo sería beneficiosa para todos, pues otorgar a los inmigrantes indocumentados una autorización de trabajo resultaría en un aumento de sus contribuciones fiscales de $40,000 millones de dólares a $137,000 millones de dólares por año, ya que la autorización de trabajo aumentaría los salarios.

Ernesto Castañeda PhD, Director del Laboratorio de Inmigración y el Centro de Estudios Latino Americanos y Latinos, American University en Washington DC.

This piece can be reproduced completely or partially with proper attribution to its author.

The English version of this text is available at the following link: https://aulablog.net/2024/08/26/mass-deportations-could-create-a-us-recession/