By Todd Eisenstadt

The role of constitutions is evolving as deeply as the countries in which they are being written. At least since 1787, constitutions have been pacts around which societal expectations converge – the written record of elite agreements on how things should be. During the “Third Wave” of democratic transitions (since the 1970s), they were viewed as precursor “contracts” to founding elections. But increasingly, constitutions are way stations rather than destinations. The content and implementation of constitutions is of course important, but the politics surrounding them can, in some cases, be more important than the clauses and amendments contained therein.

In Bolivia, Ecuador, Venezuela, and perhaps, in the near future in Paraguay, constitutional moments seem to be taking on different meanings. Optimism about constitutions as core elements of Third Wave democratization pacts is giving way to the 21st century reality of democratic backsliding, semi-authoritarianism, and hybrid regimes – making it all the more important to reconsider how to read constitutions and evaluate governments’ adherence to them. These are not stale parchments, but living narratives which represent iterations in decades-long intra-elite bargaining efforts to stall Arab Spring-like social movements (regardless of whether they actually seek to create spaces for new political actors). They represent societal gains – both real and symbolic, even with ephemeral institutional advances. This may be especially true in new and developing democracies, which need government services, constitutions that improve fairness and equity, and implementation of those commitments. Developed democracies fall short too, but in developing countries new to the art of promulgating democratic constitutions, these shortcomings are more transparent as they are less proficiently hidden from view.

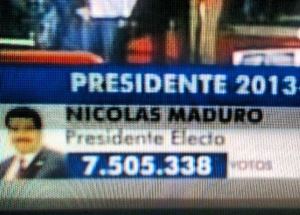

We need an intellectual space where Madison’s Dilemma – how to empower citizens without overpowering political institutions with the tyranny that unruly majorities can bring – meets Hugo Chávez’ shadow. Chávez, who was obsessed with linking the Boliviarian Union of nations via new trade agreements and political arrangements, sought to empower himself and his political allies in the guise of solomonic constitutional reform to consolidate democracy. Observers have long criticized “window dressing institutions” in the electoral arena, as evident in studies of “electoral engineering” and “sham elections.” While “sham constitutions” – a phrase that may ring too loudly – require more subtlety and political craftsmanship, we do need to question the longstanding stylization of constitutions as the “last word” (literally) on a nation’s quality of democracy. There is much to learn, and a conference held last week at American University by CLALS Affiliate Rob Albro, SIS Researcher Carl LeVan, and I, and sponsored by the Latin American Studies Association and the Mellon Foundation, made some headway in finding new ways to conceive of constitutions not as the “final word,” but only as the most recent one.