By Claudio Grossman*

President Piñera calls for agreements on coronavirus crisis and on social protection plan, jobs and economic reactivation/ Prensa Presidencia, Gobierno de Chile/ Public Domain

Chilean President Sebastián Piñera, after several months of relative calm stemming from political agreements and social policies forged last November, now faces a more complex and potentially dangerous set of challenges. Until last week, it seemed that the political scenario, while complicated, could turn better for him. A broad agreement to hold a referendum on reform of what remained of Pinochet’s Constitution – perceived as the obstacle to fair pensions, access to quality health and education – was signed in November by all the political actors in the country (except the Communists, some of their allies, and other groups on the left).

- The agreement is credited with having an important impact in reducing public demonstrations demanding social change despite continued dissatisfaction with the government and the political system in general. By creating a path for transformation, it also contributed to significantly reducing public tolerance for violent actions such as looting, burning Metro stations, and attacks on churches.

- Chile’s low public debt and significant reserves also allowed the government to adopt urgent economic measures to address at least some of the most extreme examples of unfairness (e.g., meager pensions).

- In response to national and international human rights observers, including the UN and Organization of American States (OAS), identifying serious violations of human rights during the social protests, the government announced plans to undertake reforms – notably of the Carabineros. They are the police body blamed for weak intelligence-gathering and training and for its inability to maintain public order in accordance with human rights norms.

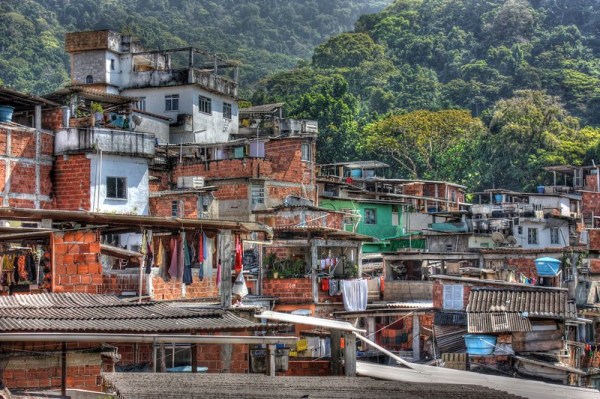

While Piñera’s popularity remained in the single digits until March – his own political base had become disillusioned with his strategy of constitutional reform – the social conflict appeared mostly channeled in the legal, institutional framework of Chilean society. The Chilean summer, during which the country typically moves in slow motion, also helped reduce social tensions. When the first wave of COVID‑19 hit Chile in March, the reaction of the government – a selective quarantine strategy focusing on areas with the most cases – seemed to be containing the spread of the virus without shutting down the whole economy. The health system was not overwhelmed; Congress, the Judiciary, and other institutions continued to work; and civil society operated freely. Piñera’s approval in the country rose from a squalid 9 percent to 28 percent. Congress, where the government does not have a majority, agreed to move the referendum from April to October – showing an important degree of consensus in the political system. The President’s fortunes might shift, however, as the virus moved from affluent neighborhoods to the more populous barrios in Santiago.

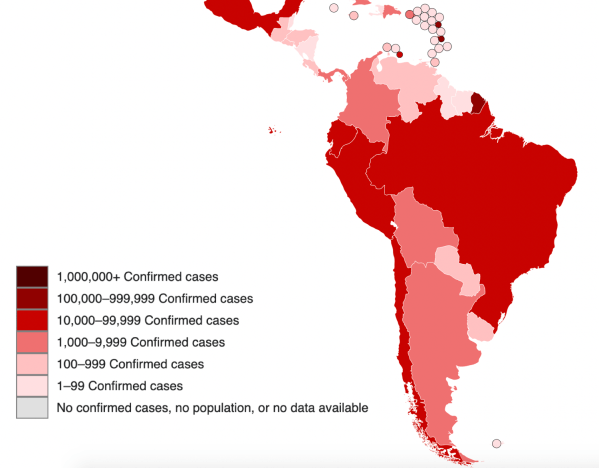

- The infection has increased exponentially, forcing the hand of the government to announce on May 13 a total quarantine of the sprawling Metropolitan Region (MR), affecting almost 8 million people. Piñera announced that the government would start distributing food packages to 2.5 million low-income households, but protests – driven by complaints that it was too little and too late – followed almost immediately. Santiago again experienced barricades in some neighborhoods and renewed clashes with the police. Some protesters claimed that distributions have privileged some areas based on political grounds. For others, some, if not all, of the protests might have been politically motivated.

As the numbers of infections continue to increase, it seems that the quarantine will not cease soon, with the danger of an increase in protests and calls for social reform fueled this time by the lack of work and means of subsistence of millions in the MR. In the dramatic context created by COVID‑19, a crucial question is whether the current political path – increased social assistance and the Referendum in October – will be feasible. The forthcoming flu season in Chile (June-August) can only compound an already grave situation and bring into sharper relief underlying social tensions.

- Postponement of the referendum as well as other elections due to take place this year can happen only by legal changes that require the opposition’s agreement. In light of the serious challenges facing Chile, broadening the base of governability of the country might be a daunting task. The President and his center-right coalition and a divided opposition might encounter great difficulty finding creative formulas to identify and implement common goals. Politics, and in particular democratic politics, need to respond properly to the gravity of the tremendous economic and social impact of COVID‑19, including seeking to achieve substantive agreements encompassing basic principles to be included in a possible new Constitution. While it is too soon to tell what will happen, time is running short.

May 26, 2020

* Claudio Grossman is Dean Emeritus and a professor at the Washington College of Law.