By CLALS Staff

World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim and Haitian President Michel Martelly / Photo credit: World Bank Photo Collection / Foter / CC-BY-NC-ND

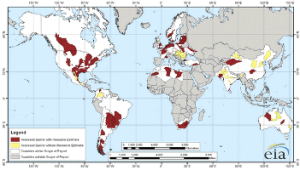

Half way through his term, President Martelly and his opponents have shown the same weak leadership and shallow commitment to democracy and transparency that has long plagued Haitian politics. The IMF recently reported preliminary data indicating that Haiti’s GDP grew around 4 percent in FY2013; that inflation dropped from almost 8 percent to 4.5 percent; and that, although the fiscal deficit was larger than planned, domestic revenues were in line with projections. On the streets, however, popular suffering shows no sign of abating. Some 170,000 remain homeless since the earthquake almost four years ago; hundreds of thousands still have no prospect of employment, and poverty rates remain sky-high. Suspicions about the whereabouts of more than a billion dollars in foreign aid are growing. The World Bank last week criticized the lack of government transparency regarding funds from Venezuela’s “Petrocaribe” program, worth about $300 million a year to Haiti, and repeated its call for an end to the government’s use of “non-compete” contracts. Corruption, a perennial concern, was a main theme of several large protests last month, involving thousands of citizens demanding Martelly’s resignation.

United Nations officials have repeatedly called on Haiti to hold parliamentary elections originally scheduled for two years ago. The lower house of parliament in November passed a bill protecting the tenure of certain members of the senate – which the UN Secretary General’s senior representative in Haiti praised as “an important step for the organization of inclusive, transparent, and democratic elections” – but myriad other preparations remain undone. The UN last August found that failure to hold elections by next month “runs the risk of [the Parliament] becoming inoperative,” but the Security Council went ahead and renewed the MINUSTAH mission for yet another year, albeit with fewer troops and police.

Donor fatigue – when the international community tires of lending a hand – seems to have been overtaken by donor disinterest, and the Haitian political elite appears much obliged. Martelly, whose stage name was Sweet Micky during his singing career, has failed to use his fame and charm to promote serious reform among Haitians, as he promised, nor has he weaned his government and its supporters off the lucre of corruption. His detractors, like those organized against Presidents Préval and Aristide before him, are better at mobilizing opposition than they are at mustering support for any political alternatives. The Obama Administration’s commitment after the earthquake to help Haiti “build back better” has faded. A central element of its vision was construction of an industrial park in northern Haiti, which more than a year after its inauguration has created fewer than 2,000 of the 65,000 jobs it promised. As long as Haitians and their international supporters are satisfied with bandaid solutions to systemic problems, the country will wallow in its misery until the next crisis makes things yet worse again.