By Robert A. Blecker*

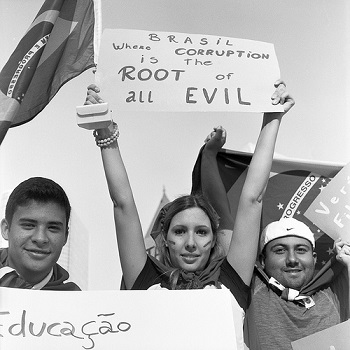

Photo credit: Alex Rubystone / Foter / Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Twenty years after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect, it is clear that the promises made by Mexican President Carlos Salinas and U.S. President Bill Clinton – that the accord would make Mexico “a first-world country” and halt the migration of Mexican workers to the United States – have not been fulfilled. In Salinas’s famous words, Mexico would “export goods, not people.” But the number of undocumented Mexican immigrants in the United States rose by a conservatively estimated 3 to 4 million during the first two decades of NAFTA, and millions more were apprehended at the border and deported. The reasons why immigration flows accelerated post-NAFTA are not hard to discern.

- NAFTA fostered integration of Mexican industries into global supply chains targeted at the U.S. market, accelerating Mexico’s transformation into a major exporter of manufactured goods. Nearly one million manufacturing jobs were created there in the first seven years of NAFTA (1994-2000). But this job growth was offset by similar job losses in agriculture, and manufacturing employment has fallen by about a half million since 2001. The net increase in manufacturing employment from 1993 to 2013 was only about 400,000, less than half of the annual growth in the Mexican labor force.

- Real hourly earnings in Mexican manufacturing were no higher in 2013 than in 1994, and Mexico’s per capita income has stagnated relative to that of the United States. In 2012, typical Mexican manufacturing workers received only 16 percent as much per hour as their U.S. counterparts, down from 18 percent in 1994. Even adjusted for the lower cost of living, workers without a college degree in Mexico still earn only about one-quarter to one-third of what they can earn by moving to the United States.

The benefits of NAFTA for Mexico have been attenuated by several factors. First, Mexican export industries still largely follow the maquiladora model of doing assembly work using imported inputs, so their value-added is only a fraction of the gross value of their exports and they have few “backward linkages” to the domestic economy. Second, the Mexican government has frequently allowed the peso to become overvalued, making Mexico less competitive and driving multinational firms to locate in other countries. Third, the tremendous penetration of Chinese imports into all of North America (Canada, Mexico and U.S.), especially since China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, has displaced significant amounts of actual or potential Mexican exports. A revaluation of China’s currency, rising Chinese wages and increasing global transportation costs have recently led to some “reshoring” of manufacturing to Mexico, but employment in Mexican export industries has grown only modestly as a result.

The increased integration of North American industries through NAFTA has proved to be a mixed blessing for Mexico. U.S. booms have helped Mexico grow, but only for temporary periods, and being dependent on the U.S. market has held Mexico back since the U.S. financial crisis of 2008-2009 and the ensuing “Great Recession” and sluggish recovery. Of course, NAFTA is but one of Mexico’s constraints. The country’s restrictive monetary and fiscal policies, frequent currency overvaluation, monopolization of key domestic markets and inadequate investments in physical and human capital have also held it back. The Mexican economy still suffers from a profound dualism, in which only about one-fifth of all non-agricultural, private-sector workers are employed in large, highly productive firms, while the vast majority are employed in small- or medium-sized enterprises with low, stagnant or even falling productivity. Mexico’s experience under NAFTA certainly argues against portrayals of international trade agreements, such as the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership, as panaceas for the economic ills of Mexico or any other country. Whatever one thinks of the “reform” agenda of President Enrique Peña Nieto – which is focused on areas such as energy, education, and telecommunications – these reforms are unlikely to help Mexico break out of its slow growth trap if the foundations of the country’s trade and macroeconomic policies remain untouched.

*Dr. Blecker is a professor of economics at American University.