By Rodolfo Calderón Umaña*

Antonio / Flickr / Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Central America’s emergence as a principal transit route for illicit drugs from South America to the U.S. has given rise to local retail markets supplying users within the region. A study of three Costa Rican communities – one in greater San José and two along the Caribbean coast – highlights several factors that determine the scale and consequences of these local markets. Among the most important are the high levels of social exclusion experienced by households in these localities and residents’ motivation to become involved in the business because it offers resources (money, power and prestige) that cannot be achieved through the legitimate channels of education or quality employment. Other factors include the proximity of the communities to drug trafficking routes and the extent of previously existing demand from local consumers.

One of the most significant characteristics of local drug markets in these communities, as elsewhere, is that they are socially and territorially bounded because trust is the key factor shaping relationships between suppliers, sellers and consumers. Some local suppliers maintain direct ties to cartels, but they operate their businesses independently. Youth are assigned the most vulnerable tasks and are thus disproportionately represented among those arrested and convicted of crimes. Violence serves as the principal instrument for controlling and regulating the drug trade, and the result is that for youth in these settings violence becomes normalized as a routine form of behavior. This spawns a generalized climate of fear and insecurity, and the typical response of community residents is to retreat from public space and to isolate themselves inside their homes.

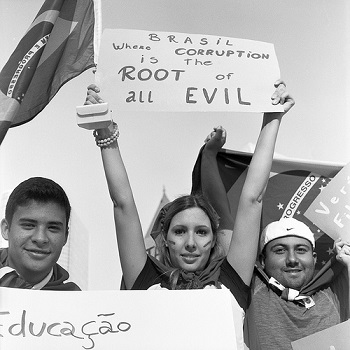

These findings support calls for new responses to the drug trade at the community level. Central American governments, encouraged to a significant degree by U.S. programs, have tended to emphasize repressing and “combatting” the scourge of drug trafficking, yet where this approach has been implemented – particularly in Central America’s Northern Triangle — social problems have only gotten worse. In Costa Rica, it’s not too late to undertake a comprehensive strategic review of policies in this domain and to bolster programs to stabilize affected areas. Particularly if designed and implemented from the bottom up, programs can identify and reach out to vulnerable residents before they are drawn into drug micro-markets as vendors, consumers, or both. Vocational training programs matched to real employment opportunities are absolutely fundamental – to reduce residents’ social exclusion. Our research findings indicate that enhancement of public spaces where community residents can congregate and initiatives focused on building trust between communities at risk and representatives of the state can also be highly productive. Costa Rica is at a critical juncture: it can either sustain and expand the participatory policy frameworks that buttress community cohesion and resilience or run the risk of falling into the devastating spiral of delinquency and violence that has plagued its neighbors in the Northern Triangle.

*Dr. Calderón Umaña is a researcher at FLACSO-Costa Rica. The study is being conducted by FLACSO-Costa Rica with funding from the International Development Research Centre.