By Carolina Sampó*

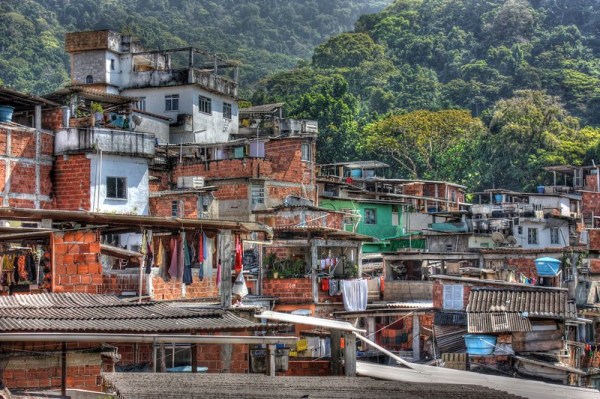

Favela Villa Canoas, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil/Phillip Ritz/Flickr/Creative Commons License (not modified)

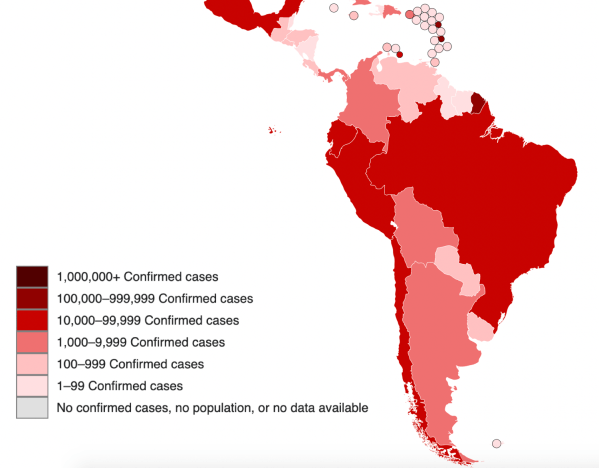

Latin American criminal organizations have faced some new challenges during the coronavirus pandemic – such as disruptions in transportation routes and markets – but they have also exploited opportunities to expand operations in ways that further threaten governments’ control in vulnerable communities.

- Shelter-in-place controls in the region and the United States have complicated the groups’ most profitable business area: drug trafficking. Moreover, breaks in supply chains, especially those related to chemical precursors from China, have caused shortages of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid preferred by U.S. drug users, and ingredients used to make methamphetamines.

- Trafficking of cocaine and other plant-based drugs has not stopped within Latin America, although some reduction in their movement to market has driven up prices somewhat. Quarantines have posed new difficulties for transportation, but traffickers usually avoid legal border crossings and pass through areas with no or minimal government presence anyway. Governments have also moved detection and interdiction resources elsewhere. Brazil, as the region’s main consumer, still seems to be receiving regular shipments of cocaine.

- Shipping drugs outside the region has been more difficult because airports are closed and commercial ship traffic has declined, but criminal organizations have accepted to run the risks of continuing their own maritime activities, which raises the price to consumers. Authorities say that cocaine shipments tend to be large – over one ton – and narco-submarines are being used.

Supply and demand have both declined during the coronavirus outbreak, but prices of meth and synthetic opioids have risen considerably – some even tripling in recent weeks, according to U.S. official sources. Demand from consumers of illicit drugs at parties is down with the implementation of social distancing, but dealers in food delivery services are distributing their merchandise directly to users’ homes. Supply and demand seem to be balanced, but dealers are charging higher prices for their enhanced service and greater risks.

As in the past, criminal organizations are showing high adaptability. International experts report the groups are increasingly getting involved in cybercrime. They have also been caught peddling counterfeit medical items. Interpol has seized substandard masks and sanitizers as well as drugs the gangs claim will help people combat the virus. The pandemic has also enabled criminals to deepen their ties with vulnerable communities, such as by providing essential goods and services.

- They are consolidating criminal governance in the communities where they play the role of social order providers. In the slums in Rio de Janeiro, for example, the criminal organizations have been the ones to enforce lockdowns to stop the spread of COVID‑19. Where criminal organizations cannot guarantee social order, they use violence or cooptation to establish territorial control. And they continue efforts to expand prison control, using jails to recruit members and build their power base. During the coronavirus outbreak, the gangs have organized riots and jailbreak attempts in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Peru, and Venezuela. Power in the prisons projects into power on the streets.

The pandemic has forced governments to prioritize resources on the health and economic crises it is causing, and efforts to control criminal organizations have by necessity been more lax. The gangs are also scrambling to return to “normalcy,” but they are again demonstrating greater adaptability than are the governments.

- Governments have no easy solution. While organized crime is diversifying its portfolio of activities, reinforcing its territorial control, building its prison base, and recruiting new members – exploiting the economic and social situation – governments have little choice but to beef up efforts any way they can domestically while paying special attention to cooperation with neighboring countries facing similar challenges, in hopes of hemming in the criminal organizations. It is a huge challenge – against difficult odds – but perhaps the pandemic also gives governments a one-time opportunity to hit the gangs at a time that they face challenges too.

May 22, 2020

* Carolina Sampó is Coordinator of the Center for Studies on Transnational Organized Crime (CeCOT), International Relations Institute, La Plata National University, and a researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (Conicet) and Professor at the Buenos Aires University.