By Dr. Susana Nudelsman

Latin America is a region of great contrasts that currently faces serious challenges and also great opportunities. At the global level, the current outlook is uncertain. Forecasts for 2025 suggest that the world economy will experience moderate growth. In particular, the pace of growth shows signs of slowing in both the United States and China, and a slight increase in Europe (International Monetary Fund, 2025).

Emerging economies are likely to continue contributing to global growth, but they are also vulnerable to a slowdown in capital inflows and increased financial selectivity (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2025). Escalating trade tensions, uncertainty surrounding global interest rates, and the increasing frequency and severity of climate-related incidents increase long-term risks. Moreover, persistent geopolitical tensions and protectionist policies are making supply chains highly volatile (Inter-American Development Bank, 2025).

At the domestic level, Latin American countries face a mixed panorama. While the dramatic changes in socioeconomic conditions have significantly impacted the post-pandemic recovery, it has also presented opportunities for resource mobilization. However, current regional records indicate that the balance of payments will continue to be impacted by external vulnerability. Domestic demand is expected to remain weak, and employment growth is anticipated to be lower than in previous years, although informality and unemployment are expected to show slight improvements (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2025).

Inflation is expected to remain stable in 2025 and 2026 and close to target levels, but an upward trend cannot be ruled out. Although monetary policy does not necessarily have to be restrictive, ambiguous capital inflows, exchange rate volatility, and global uncertainty are impacting central banks’ policies, which must preserve stability without decelerating economic activity.

Economic growth, interest and exchange rates, as well as commodity prices, all affect fiscal sustainability. Therefore, fiscal space will remain limited, as many countries face upward pressure on spending and high borrowing costs. Similarly, in this case, one of the biggest issues facing the region’s governments is the need to take into account various restrictions without compromising economic growth.

Productivity growth remains sluggish, hindering advancements in poverty alleviation and impeding significant enhancements in living conditions. Despite a recent decrease, inequality in Latin America is higher not only in comparison with advanced countries but also with other countries of a similar level of development (Inter-American Development Bank, 2025).

Additionally, growth models in the region have struggled to foster technical advancement, which has contributed to low per capita research rates. A marginal position in global innovation, insufficient investment in innovation ecosystems, and persistent problems related to infrastructure and digital skills have prevented the region from achieving a competitive technological position.

Overall, persistent structural challenges continue to hinder long-term economic growth. Although the future is clearly complicated, the region’s ability to seize new opportunities will depend on the policy decisions taken now. Increased regional integration, pro-growth structural reforms, and stronger institutional frameworks are necessary to transition from just stable to inclusive and sustainable growth.

In particular, the global economy is experiencing sluggish growth but also abrupt changes. This scenario creates tensions and new imbalances, while also presenting significant opportunities for Latin American economies. Certainly, they have the potential to increase their integration into global markets, which in turn would lead to greater economic growth, thereby enhancing regional prosperity and diversification.

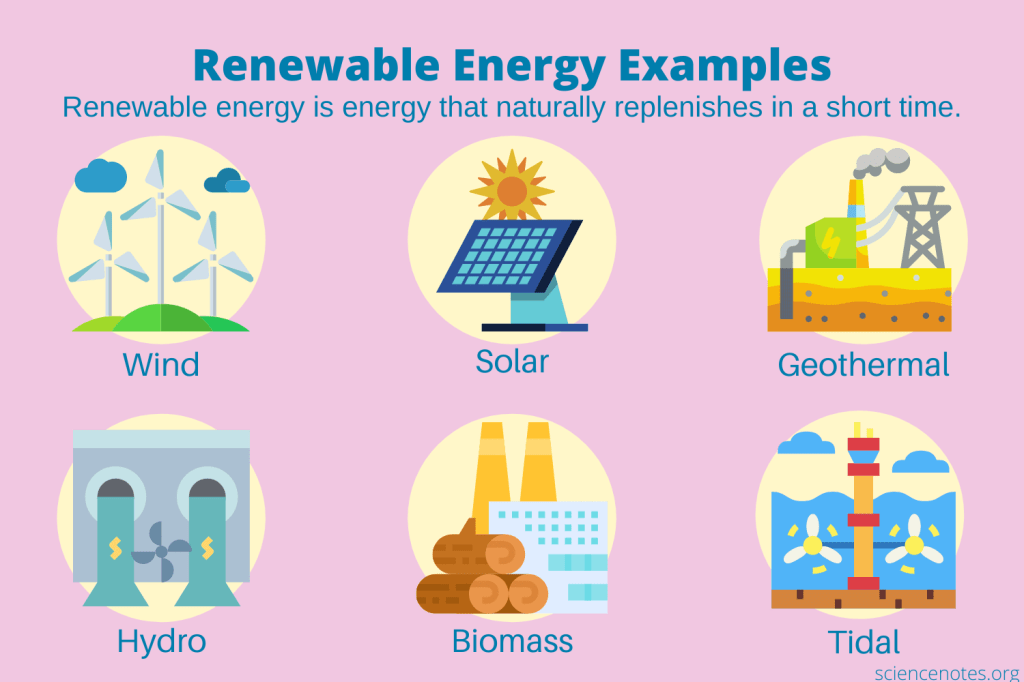

Although changing economic relationships and supply chains are not precisely good for everyone, Latin America may benefit from them in the current global environment. Thus, exploring the development of renewable energies presents a significant opportunity for the region in the context of an increasingly divided world, which is seeking greener and more sustainable growth strategies (O’Neil, 2024).

Latin America has extensive sustainable energy resources, with one-third coming from clean sources, which exceeds the global average of 20%. Additionally, 60% of its electricity already derives from renewable energy. The region is backed by abundant solar, wind, and geothermal resources, helping businesses meet climate goals and explore green hydrogen, which results in very low or zero carbon emissions. It also produces a third of global lithium and possesses significant reserves of cobalt, manganese, nickel, and rare earth elements crucial for electric vehicles, solar energy, and wind turbines.

In this respect, factors related to political economy might represent obstacles despite strict environmental policies, suggesting that to advance towards a greener economy, countries need to integrate environmental policy with an overall enhancement of institutional quality, take into account the government’s political stance on environmental policies, and assess the impact of large energy-intensive sectors within the economy.

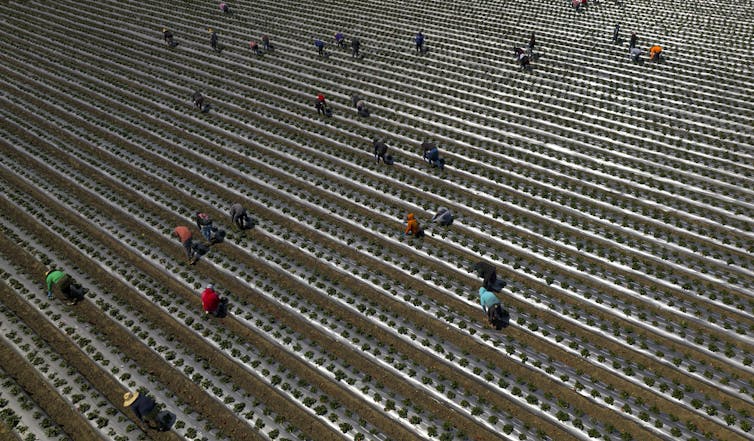

Furthermore, the shift to “friend-shoring” and “near-shoring” benefits Latin America since many nations in the region maintain enduring diplomatic, commercial, and cultural connections with the United States. Although some Latin American governments face challenges due to democratic erosion, the region continues to offer the best platform for balancing democratic governance and economic growth, as it has been the most peaceful region in terms of wars (Latinometrics, 2025).

Transitioning to clean energy poses difficulties but offers significant opportunities to generate employment, stimulate economic development, and improve energy security by decreasing dependence on fossil fuels and encouraging innovation in sustainable technologies. All in all, Latin America’s energy potential is enormous, and its leadership must act swiftly to attract stable trade and investment flows in response to evolving geopolitical and economic policies for future success.

References

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2025, Resource mobilization to finance development, Economic Survey of Latin America and the Caribbean, United Nations, ECLAC, Santiago de Chile.

Inter-American Development Bank, 2025, Regional Opportunities amid Global Shifts, 2025 Latin American and the Caribbean Economic Report, IDB, Washington DC.

International Monetary Fund, 2025, Latin America in the Current Global Environment, Regional Economic Outlook, IMF, Washington, DC.

Latinometrics, 2025, Sabías que América Latina no ha vivido una guerra territorial en más de 30 años? Latinometrics, available at https://www.linkedin.com/posts/latinometrics_sab%C3%ADas-que-am%C3%A9rica-latina-no-ha-vivido-activity-7338249978001207298-KNtw/?originalSubdomain=es

O’Neil Shannon K., 2024, Latin America’s Big Opportunity, Project Syndicate, June 10, available at https://www.project-syndicate.org/columnist/shannon-k-oneil

Susana Nudelsman is a Doctor in Economics focused on international political economy. Counselor at the Argentine Council for International Relations and visiting fellow at CLALS.