By Andrés Serbin

The seventh UNASUR head of state summit, held in Suriname in August, failed to give the organization the shot in the arm that it needed to continue developing as an effective voice for South America. Despite grandiloquent declarations that it was a “historic event” for the region, the summit was in danger of being overshadowed by several incidents. The son of Suriname´s President and summit host, Desi Bouterse, (who himself has a checkered past) was detained in Panama the day before the summit and extradited to the United States, where he faced drug- and arms-trafficking charges. (The son was subsequently charged with “attempting to support a terrorist organization” as well.) Moreover, four of the 12 UNASUR heads of state didn´t attend the Summit, and bilateral tensions between some of the participants got the meeting off to a rough start: Bolivia was irritated that Brazil gave asylum to a senator accused of corruption; Uruguay’s decision to expand a paper plant on the Paraná River peeved Argentina; Chile and Argentina were in a row regarding the Chilean airline LAN’s use of facilities in Buenos Aires; Chile and Peru continue a battle in the Hague about a territorial dispute; and Paraguay was still in limbo after being suspended from UNASUR (and MERCOSUR) after President Lugo’s removal last year by the Congress.

The seventh UNASUR head of state summit, held in Suriname in August, failed to give the organization the shot in the arm that it needed to continue developing as an effective voice for South America. Despite grandiloquent declarations that it was a “historic event” for the region, the summit was in danger of being overshadowed by several incidents. The son of Suriname´s President and summit host, Desi Bouterse, (who himself has a checkered past) was detained in Panama the day before the summit and extradited to the United States, where he faced drug- and arms-trafficking charges. (The son was subsequently charged with “attempting to support a terrorist organization” as well.) Moreover, four of the 12 UNASUR heads of state didn´t attend the Summit, and bilateral tensions between some of the participants got the meeting off to a rough start: Bolivia was irritated that Brazil gave asylum to a senator accused of corruption; Uruguay’s decision to expand a paper plant on the Paraná River peeved Argentina; Chile and Argentina were in a row regarding the Chilean airline LAN’s use of facilities in Buenos Aires; Chile and Peru continue a battle in the Hague about a territorial dispute; and Paraguay was still in limbo after being suspended from UNASUR (and MERCOSUR) after President Lugo’s removal last year by the Congress.

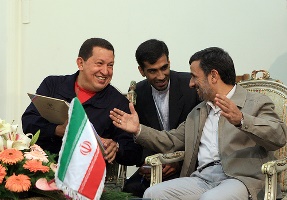

Even as the dust settled, however, UNASUR was unable to take on the most important task of the summit – appointing a new Secretary General for the organization. Despite their contrasting styles – sometimes complementary and sometimes in open competition – Presidents Chávez and Lula de Silva had driven the creation and consolidation of UNASUR after the end of the FTAA project during the Mar del Plata Summit of the Americas in 2005, but that strong leadership is not there anymore. Their absence laid bare the weak political will of most other South American leaders to consolidate the organization and to build a strong institutional basis for its development. No one, except perhaps former (and controversial) Paraguayan President Lugo has expressed interest in the job of Secretary General. It was no surprise, moreover, that the Summit was not able to advance other crucial decisions, such as the creation of the long expected Banco del Sur. A resolution condemning U.S. initiatives regarding Syria was one of the few relevant and consensual results of the Summit.

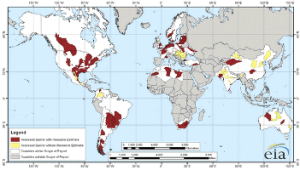

UNASUR started out as a political endeavor based on regional, instead of national, interests, and much of its earlier momentum was driven by rejection of earlier “neoliberal” attempts at regional integration and of the role of the United States in the region. Members’ new focus is clearly state-centric and political, as regional market and trade issues have been superseded by a new agenda focusing on infrastructure and communications development, energy and security agreements, global financial impact and environmental concerns. The absence of new leadership to move forward a regional agenda poses a series of challenges to this process. In the meantime, other processes continue. Paradoxically, some of the member countries are deeply involved in the creation of a new initiative – the Pacific Alliance (Alianza del Pacífico), clearly oriented towards free trade.