By Carlos Monge*

Latin American governments and business associations have tended to overstate the benefits of extractive industries during the commodities supercycle that ended in 2014-15. Resource-rich Latin American countries did experience high rates of economic growth and diminished poverty and inequality during the boom years. On the surface, this would appear to strengthen arguments that – despite their negative environmental impact – extractive industries are the key to progress, especially in resource-rich areas. Nevertheless, a closer look at data from household surveys in Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru shows that things are a bit more complicated.

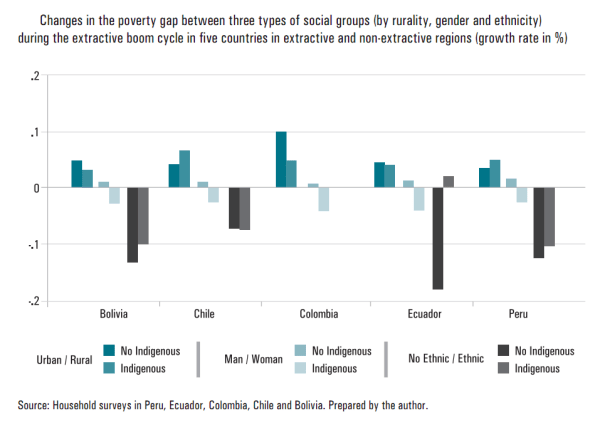

- The inequality gap between individuals, as measured on the GINI Index, has narrowed, but the gaps between groups of the population have not evolved evenly. For example, the National Resource Governance Institute (of which I’m regional director) recently completed a study of the performance of social indicators during the supercycle that concluded that the poverty gap between urban and rural populations has increased in all countries. (The report is available in English and Spanish.) In Peru and Chile, the gap increased more in territories where extractive territories are located, while in Colombia, Bolivia, and Ecuador less so. The gap between indigenous and non-indigenous populations increased only in extractive territories in Ecuador, decreasing in both extractive and non-extractive settings in the rest of the countries considered. Regarding gender, in all five countries the gap between men and women increased slightly in non-extractive territories and decreased a bit more in extractive ones.

This report establishes correlations between the increase in extractive activities, the availability of extractive rents, and patterns of inequality reflected in social indicators, but it does not establish a causal relation between such variables. For example, the data show that urban populations in Peru’s extractive regions have benefited more than rural ones – which some very preliminary research shows is probably because urban centers provide extractive projects with the goods and services they need, while less sophisticated rural areas do not. At the same time, rural populations have to compete with the extractive projects for those same urban goods and services, and with local governments for the labor force that the public sector contracts to develop infrastructure projects that are paid for through increased revenues delivered by the extractive sector. This is what we have called the “Cholo Disease.” A variation of the “Dutch Disease,” it reflects a loss of competitiveness resulting not from large exports of raw materials causing the currency to appreciate, but rather from increases in the cost of labor and of urban goods and services consumed by campesinos. However, a more definitive explanation regarding exactly how this happens in Peru and in other countries certainly needs further research.

While our data clearly show the impact of mining and hydrocarbons extraction and the resulting expenditure of extractive rents on the poverty gaps between urban and rural populations, men and women, and indigenous and non-indigenous populations, further investigation into the causes and consequences is needed. The end of the supercycle has already meant a fall in growth rates and extractive revenues, leading to a worrisome rebound in poverty rates. We are still unable to answer, however, the question of how broadly it will impact the substantial segments of Latin America’s population that emerged from poverty but remains in a vulnerable position – and how it will aggravate poverty gaps among individuals and between groups in extractive and non-extractive territories.

May 16, 2017

* Carlos Monge is Latin America Director at the Natural Resource Governance Institute in Lima.