By Ana Serra*

The Buena Vista Social Club Orchestra’s performance at the White House last week was a celebration of the ongoing normalization process between the United States and Cuba and of the musical collaboration – considered illegal at the time – that made this group possible. Playing in commemoration of Hispanic Heritage month and the Educational Excellence of Hispanics, it was the first visit to the executive mansion by a Cuban band in more than 50 years, and part of its Adiós World Farewell Tour including a number of U.S. states before traveling to Puerto Rico and Latin America. Buena Vista Social Club (BVSC) is a brand, starting as a 1940s club in Havana and revived by a 1997 album produced by Ry Cooder with Cuban and US musicians, a 1999 documentary film directed by Wim Wenders (chronicling concerts in Amsterdam and New York), and decades of fame-garnering recognition of Grammies and film awards. At a time that the U.S. administration is taking steps to relax the terms of the embargo, the invitation auspiciously recognized Ry Cooder’s inaugural ice-breaker, which was investigated as a violation of the Trading with the Enemy Act. While tied to the commercial success of the band, the concert inadvertently has progressive implications in a racial context.

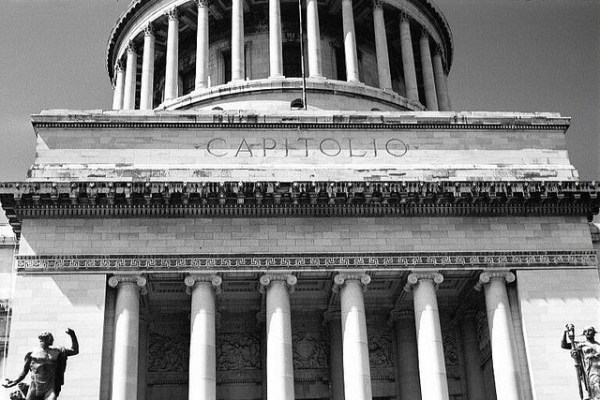

The invitation to play at the White House amounts to a diplomatic gesture, and as such it was both cautious and optimistic. The event resonated with many other people-to-people exchanges that have made thaw a reality, and highlighted the prominence of Americans of Cuban descent among Hispanics in the U.S. The band is tried and true – if fully predictable – in its powerful evocations of a memorable past. Its traditional musicians evoke the Havana music scene of the 1940s, a time of intense exchange and collaboration between Cuban and U.S. musicians. In addition, it may cause for some a nostalgia for a supposedly harmonic relationship between the two countries, despite decades of strong U.S. intervention in political and economic affairs during the two administrations of Fulgencio Batista. The album’s son, bolero, guajira, and danzón rhythms do not challenge expectations and the lyrics talk about love, beautiful women, and tropical landscapes. Ry Cooder’s role in forming the original band – he apparently brought piano virtuoso Rubén González away from a shoe-shining job – represents the current dream of many art representatives hoping to go down to Cuba and “discover” or “bring to light” hidden talent.

Fans of Cuban music may be disappointed that far more interesting Cuban musicians – in terms of novel song styles or political messages – were not invited. BVSC’s tunes have become so familiar as to make the minds of listeners numb: they have been played to exhaustion in tourist sites in Havana, and added to the ambiance of many a foreign venue aiming to evoke the irresistible rhythms of Latin American music. A silver lining, however, are the progressive implications of what the band represents in a racial context. The original Buena Vista Social Club was a so-called “club de negros” in the 1940s, in which the 1997 BVSC performer Compay Segundo had played. These clubs were closed down after the 1959 revolution, since their emphasis on black identity was deemed divisive. At the time of #blacklivesmatter in the United States, it is fitting that the first African-American president hosted this historic band in the White House. Beyond the problematic background of a beautiful diplomatic gesture the event establishes a bridge between some of the common struggles in the U.S. and Cuba.

October 22, 2015

* Ana Serra is an Associate Professor of Spanish and Latin American Studies in the Department of World Languages and Cultures at American University.