By Ernesto Castañeda

If you are a young student in the United States and you are worried that you, a classmate, or a loved one could be deported by ICE agents, as you have seen on social media, TV, or in your neighborhood, this short text is for you.

School dance. Photo by Ernesto Castañeda.

Why are people in pseudo-military clothes and vests with the initials ICE, HSI, CBP,* and others patrolling the streets and aggressively arresting people in public? It all starts with the popular but dangerous idea that a country must have closed borders, allowing only invited people to pass through. This makes sense for private houses, schools, and other large private institutions, but cities and countries do not work like that. Think about it most people born in the United States can move in their cities, towns, as well as to other cities or towns in the 50 states without having to ask permission from any political authority. They can even move to Guam, the Virgin Islands, or Puerto Rico.

*ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement], HSI [Homeland Security Investigations], CBP [U.S. Customs and Border Protection, agency that houses the Border Patrol which has now also being mobilized to both coast and Chicago] are all immigration enforcement agencies within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Under the current administration other federal and local agencies have also been assigned to help carry out raids and aid in deportation efforts.

People in Any Country Are Not All the Same

Another dangerous myth is that all the people in a country must share a language, culture, and even look the same, as if related by blood. But countries are not big extended families, so this is a fable. But many adults believe this was true in the past and want it to happen soon in the places where they live. As you know, not everyone is the same. Even within the same family, a student club, or sports team, people have differences that make them who they are.

People in some large cities complain about a few people around them speaking a different language in the streets or having a different religion. This is not new; some people have always done so in any booming city.

Even While Most People Stay Put Most of the Time, Mobility is Normal

Many people go to other countries to travel, study, work, or visit family members and friends. Most people get visas, which are permits from a country’s government to visit or move in with permission. People from the United States and Europe rarely need visas to visit other countries, but it is not the same the other way around. People from most of Africa, Asia, and Latin America need vetted visas to visit Europe, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, or Australia.

In some exceptional cases, people have to leave the countries where they were born because of war or persecution because of their religion, ethnicity, or political views. It may be hard for them to get immigration visas after that. Other countries are supposed to provide refuge, a safe place to stay for groups facing persecution. But many countries’ governments like to look the other way or play hot potato with people.

Work Abroad is Often More Available than Working Papers

Other people may have informal verbal (spoken) job offers from restaurants, farms, and small businesses in the United States, but they cannot get visas because the people in charge of approving visas in U.S. consulates abroad think those people would stay in the country, and they think they do not have the savings and education to make them “desirable” to come to the United States. These are not necessarily the views of the people approving visas, but the informal instructions they are told to follow by their bosses.

Nonetheless, some people from towns with a long history of long-distance migration from point A to B have the contacts, paths, and know-how to go to other countries without the U.S. government’s permission. This is what people refer to as “illegal immigration.”

Remember, we should not use the term illegal to name a person, because a living human being cannot be “illegal,” but people can commit acts that go against the law, in this case, entering another country without getting their passport inspected and stamped.

“No Human Being is Illegal.” Elie Wiesel

People without a legal immigration status, who we can call undocumented, are not automatically bad people. They are just caught in a hard and vulnerable situation. Some adults say they should respect the law of a country and “get in line,” but for many of them there is no line to wait in. And for some of the people with close family members legally in the U.S., the wait in line to reunite can be ten years of longer. Therefore, some people live for over a decade away from their parents or minor children. As we recount in the book, Reunited: Family Separation and Central American Youth Migration.

Middle schoolers playing soccer. Photo by Ernesto Castañeda.

For most of U.S. history, lawyers have not labeled this a crime but more a “civil” infraction, something like a minor driving infraction, such as driving without insurance, or watching a movie without paying a ticket. But in those examples, people are getting something without paying or putting others at potential financial risk. Immigrants come to the U.S. to work, to pay for all of their expenses, those of their family members, and to send money to loved ones who stayed in the places they came from. Preventing people from moving to a country, and more appropriately to a particular city or neighborhood, even if they can pay for their housing, is like public parks or libraries not allowing only certain people in.

The problem with the label of “illegal” (rude name-calling) is that it conjures or brings together the idea of coming as a family without a visa, along with generalizations and stereotypes that only people who are poor and of different races are “illegal.” That “illegals” are inferior, potentially dangerous criminals, a threat to the homogeneity (looking or being similar) of a country. These all false.

In recent U.S. history, the label of “illegality” has been applied to people from Mexico and Central America with limited English and/or African and indigenous features working in sectors such as agriculture, construction, contracting, food preparation, etc. There are business owners who are undocumented as well as people from Canada and Europe, but it is easier for them “to pass.”

Immigrants who commit violent crimes are not immune (protected) from being stopped by police and imprisoned. But for many decades, people in the news have said that people without papers are dangerous and taking things from U.S. citizens. Many adults have come to believe this after hearing it so many times.

Some politicians run for office sometimes with as little as promising to “get rid of” all the undocumented people in a country. This has been the case of President Trump, and he has acted on this words. His team has set ambitious goals to find people without valid visas or immigration permits and to remove them from the country, which is what we call deportations. He and his team campaigned on closing the border to new arrivals, deporting people with criminal convictions, and with the signs and slogans of mass deportation.

How do you carry out mass deportations quickly in a country with over 350 million people, where less than 3% of the population is undocumented?

Unlike a classroom, there is no list of everyone living in the U.S. that includes everyone’s immigration status. So, this federal administration is trying to reach its goal is by deporting under any pretext some people who are renewing visas, trying to get papers to stay longer, become citizens, or get protection from deportation because they fear for their safety if they were sent back to dangerous places.

Another shortcut by ICE is to go to places where many stereotypical potentially undocumented immigrants gather and stop and ask for papers from people based only on their physical appearance, job, and accent. (Lawyers call this racial profiling).

Communities with many Latinos are specially afraid about deportations hitting close to home. Over 68,000 people are in immigration detention centers at the end, so of them will be let go after proving they are citizens or have valid permits. Many others will eventually be deported without their family members.

Because of this, families with undocumented members are afraid of spending time in public and may always fear it may be their last day together. So, it is important to be patient and supportive of people who could be in that situation. It is understandable if your classmates or even friends do not want to talk about this. Their parents may have told them not to share their immigration status or that of their parents, afraid that it could be used against them. Many live with the continuous fear that an enemy could call la migra (ICE) on them. The have lived with this fear sometimes for decades.

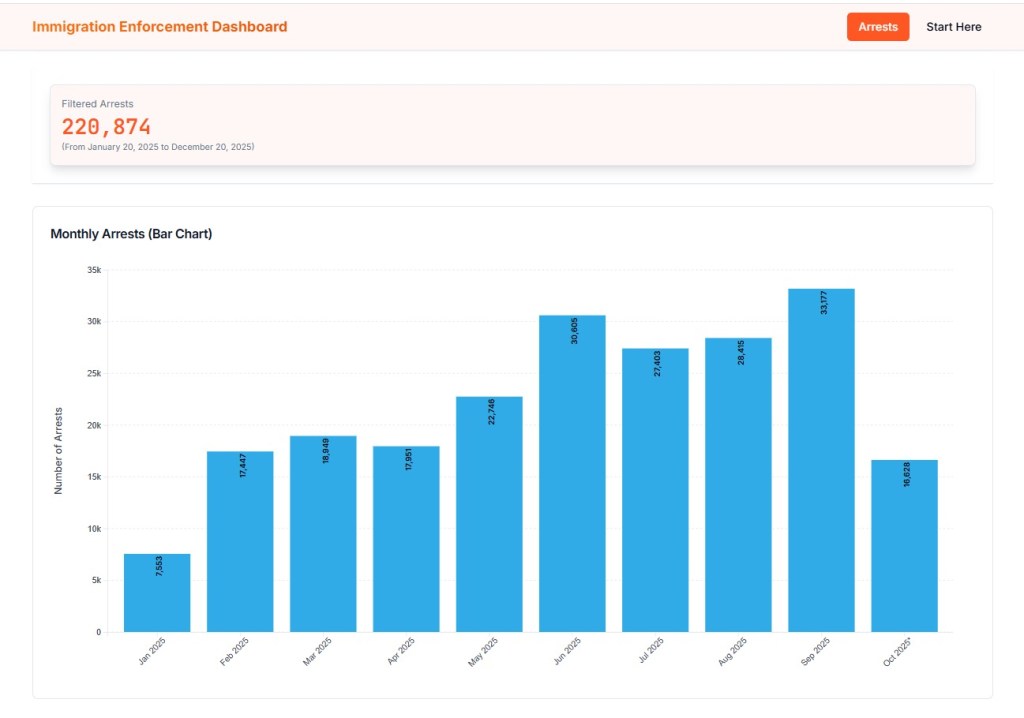

ICE Arrests from Immigration Enforcement Dashboard

People who are undocumented have to try to act perfectly

Afraid about her only daughter being caught by surprise, an interviewee we talked to confidentially, recounts that she told her 13-year-old daughter this year that she was “illegal,” and that she should be careful not to skip class, misbehave, or even think about experimenting with illegal drugs, alcohol, or marijuana because this could cause her deportation and that of her mother and maybe other family members too.

She had never before realized she was undocumented; she thought she was like anyone else in her class, and she is and so she is at risk of deportation. She cannot help but be worried, but how worried should her best friends be? Well, there were around 11 million individuals who were undocumented when Trump became president again on January 20, 2025. Because of changes to immigration laws, procedures, and programs, there may be 14 million people out of status a the end of 2026.

In 2025, the Trump admin, with its aggressive policing, raiding, and detaining, forcibly deported between 200k and 600k people. Self-deportation is a luxury that many immigrants do not have. The official estimates for this are not credible.

So, let’s do some simple math for the probability of being forcible deported by DHS by dividing the maximum estimate for 2025 deportation by a medium-high estimate for the number of undocumented: 600,000/14,000,000=.04 or 4%. This is the probability that an undocumented person is deported each year that these mass deportation goals continue along with large federal agent deployments and police collaboration in some localities [287(g) agreements]. The probability of being detained while attending an immigration court appointment is also low. So, while it is possible this may happen to you, your mom, or your friend, most immigrants won’t be deported. Clearly, the likelihood varies by location. In some places, other certain groups are targeted, like Somalis in the Twin Cities recently. But detaining people and deporting them in this way is very expensive, damaging for the U.S. economy and society, and currently very unpopular. Over 60% percent of U.S. adults oppose these policies. Tell the people you know in this situation not to despair or give up.

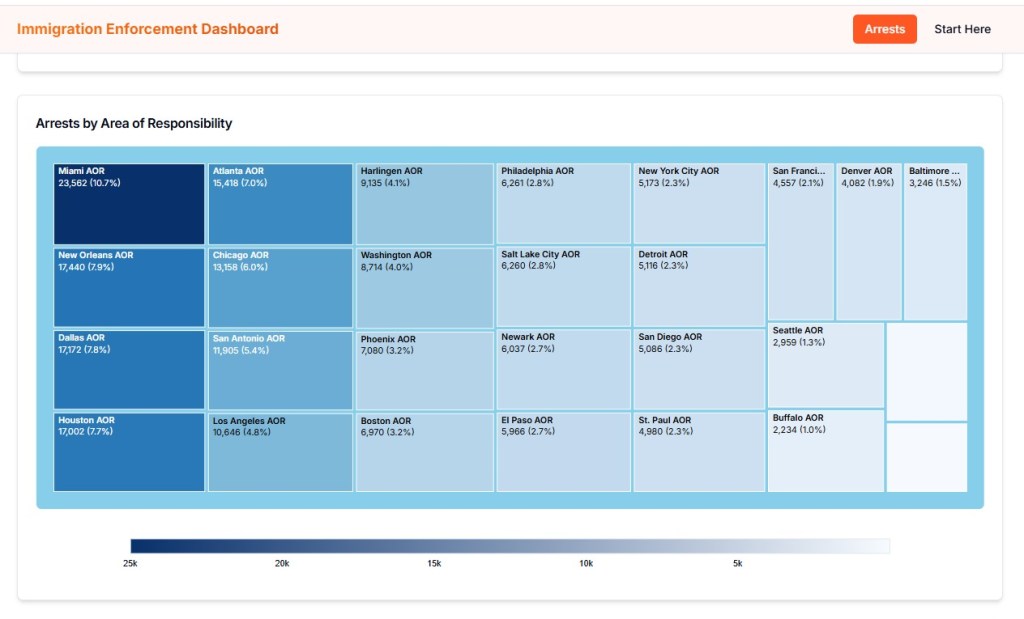

Deportation by City. Immigration Enforcement Dashboard

Despite sad cases about children receiving cancer treatment, nurses and care worker women being deported, the numbers show that, because of profiling, most of the people deported are working-age men from Mexico, Guatemala, and Honduras. Over 70% of them have no criminal record whatsoever, and only a very small percentage have a violent crime conviction. Meaning most people are innocent hard workers, fathers, sons, but they have been deported because they look like the stereotype. There are good and bad people everywhere. This may remind you of why some teachers and adults may tell you the importance of not generalizing, not falling for common stereotypes and prejudices, and of getting to know people from all backgrounds and with origins in all parts of the world. Learning how to put yourself in their shoes is the best way to understand them, comfort them, and protect them, in the future, by changing the way we aim to deal with undocumented immigration, not by mass deportations or having people afraid of deportation, but by giving them a way to become documented through new laws voted in Congress. Your care and your voice matter.

Ernesto Castañeda is a Professor at American University, where he leads the Immigration Lab and the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies. He has been studying immigration scientifically for over 20 years and has written many books on the subject, among them “Reunited: Family Separation and Central American Youth Migration” and “Immigration Realities: Challenging Common Misperceptions.”