By Marcus Rocha*

Brazilian President Temer (right) and General Villas Bôas (left) shake hands. / Romério Cunha / Flickr / Creative Commons

Brazilian President Temer is increasing the armed forces’ role in security matters, especially in Rio de Janeiro, in what appears to be a populist measure to increase his odds in the October election should he decide to run. Although General Villas Bôas, commanding general of Brazilian Army, has cautioned about the limitations on the military’s ability to carry out civilian security operations, the Army has generally accepted the mission and used it as pretext for more funding and more legal protection from prosecution. Governments have increased the use of the Armed Forces for security in Rio on a number of occasions in the last 26 years, including during international conferences, a Papal visit, and surges in drug violence in the favelas. Preparing for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics, then-President Dilma Rousseff also favored using the military over state police for many security functions. Military units have usually operated under Decretos de Garantia de Lei e Ordem to circumvent Constitutional prohibitions on their role in civilian policing.

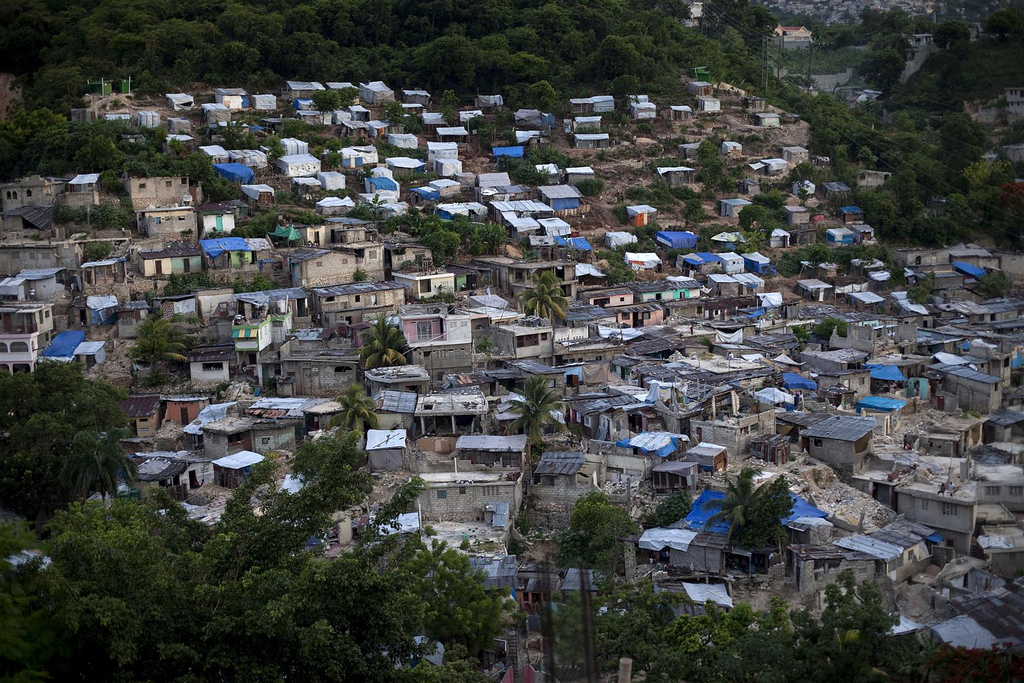

- This approach has been criticized for both its fiscal and human costs. During a 15-month period beginning in 2014, when the Armed Forces occupied Favela da Maré (a group of 16 communities in Rio), the operation used 85 percent of both the military personnel and of the $200 million budget used during Brazil’s 11 years of involvement in Haiti peacekeeping under MINUSTAH. Violations against slum residents were reported, and polls showed that most of the inhabitants of Maré did not feel safer with the Army in the streets.

- Congress last year approved a law initially proposed in 2003 allowing cases of civilians killed by the military in such operations to be tried in special military courts – fueling popular concern that the extra protections for troops would give them a “license to kill.” Army commander Villas Bôas had lobbied for the law. The internal security mission gives the military leverage for resources, but generals acknowledge that soldiers aren’t trained to deal with security in urban areas. Villas Bôas has said publicly that his forces “don’t like this kind of deployment”; are concerned it hurts their image; and lament that affected areas return to status quo after they depart. Villas Bôas has spoken also of “fears of the contamination” of troops by organized crime.

Temer’s moves go beyond his predecessors’ in that federal authority, rather than supplementing local officials, is subordinating them for the first time under the 1988 Constitution. The interventor assumes the governor’s authority for the entire state’s security, with power to command both civilian and military units.

- Temer has also announced the creation of a new Ministry of Public Security focused only on security – an issue normally under the states’ exclusive purview. While the ministry would provide more federal funds and coordination to anticrime initiatives, specialists note that the move also would give the President increased influence over the anti-corruption investigations that have rattled his Administration (among many others). The Brazilian Federal Police, now under the Ministry of Justice and widely speculated to move to the newly created Ministry, is a key player in the years-long Lava Jato Temer’s announcement has prompted fear – including among Lava Jato investigators, according to press – that changes in the chain of command could undermine efforts against corruption under the guise of focusing the resources in public security.

Temer’s actions suggest greater concern about polls than improved security. With national elections just seven months away, he has single-digit approval ratings and has been unable to push through signature initiatives, such as pension reform. Of the three top concerns in the polls – health care, corruption, and security – he has chosen the latter as the centerpiece of his agenda for the election, even though he has said he will not run. Temer may find confirmation of his strategy in a drop in the crime rate during Carnival this month, but the use of the Armed Forces against drug-trafficking, organized crime, gangs, and other security challenges has proved dubious at best in Colombia, Mexico, and elsewhere. In Rio de Janeiro, mafias made up of former Army, civilian police, and firemen dominate the drug trade and even services like gas, light and cable TV. The increased use of the military also has potentially profound consequences for human rights, military professionalization, the development of civilian institutions, and the broader embrace of rule of law. Increased federal intervention in Rio and elsewhere responds to short-term political interests with long-term outcomes that will only make things worse.

February 26, 2018

*Marcus Rocha is a CLALS Research Fellow.