By Andrew Johnson*

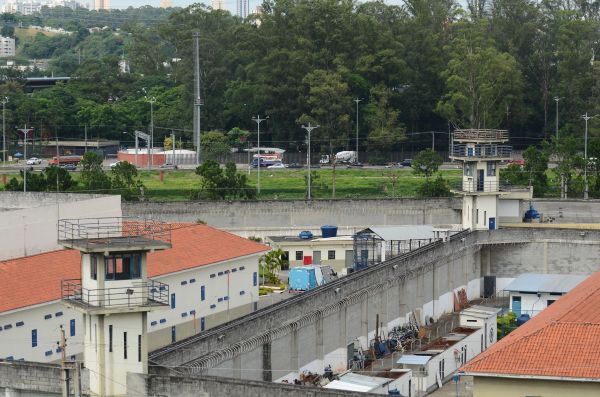

An interim detention center in São Paulo, Brazil. / Rovena Rosa / Agência Brasil / Wikimedia / Creative Commons

It has been a horrific start to 2017 in the Brazilian prison system, and reversing the trend will take much more than increased public funding. A wave of violence began on New Year’s Day when 56 inmates were killed during a riot inside of a penitentiary in Manaus. A series of deadly inmate uprisings followed that massacre, bringing the number of inmates killed this month to 120. Macabre images of inmates’ decapitated corpses strewn about prison yards captured on cellphone cameras and posted to the internet reminded Brazilians that overcrowding, a weak state presence, and institutionalized gang power have combined to make Brazilian prisons – with over 600,000 inmates – tinderboxes ready to ignite at almost any time.

- During a year I spent conducting fieldwork inside jails and prisons in Rio de Janeiro for a book and documentary film in 2011, I saw inmates crammed into cells at three and four times their intended capacity. On the worst nights, men unable to find space on the floor or a concrete bunk tied their torsos to the steel gates with t-shirts and attempted to sleep while standing.

- The Comando Vermelho and other gangs controlled entire cellblocks and used smuggled cell phones and strategic visitors to maintain regular contact with leadership. This communications capability and weapons caches inside the cellblocks enabled them to act as the de facto government. Prison guards knew that they were outgunned and outnumbered, and they knew their off-duty lives could be easily extinguished by an order initiated inside the prison. January’s riots revealed how thin the veneer of state control really is inside.

Impassioned pleas, prompted by the riots, to reduce overcrowding and provide more resources to Brazil’s prison system are being launched in a time of austerity. The Brazilian Senate recently approved legislation that could freeze public spending for the next 20 years. Public investment would certainly reduce the likelihood of future riots, but the crisis in Brazil’s jails and penitentiaries is not caused simply by underfunding. It is the result of decades of the state treating inmates, and the residents of the neighborhoods where most of them were born, as less than full citizens. Pastor Antonio Carlos Costa, leader of the human rights organization Rio de Paz, told me the state and public’s reactions to the many thousands killed by the police and hundreds murdered in prisons each year were limited because “they are poor people, people with dark skin, people considered killable. These are deaths that don’t shock us, they don’t make the Brazilian cry.”

There is no excuse or justifiable defense for the inmates involved in the 120 murders that occurred inside Brazilian prisons this month. It was an inhumane slaughter propelled by gangs, greed, and a power grab. But the solution to Brazil’s profoundly troubled prison system lies much deeper than increasing public spending or reducing overcrowding. Refusing to treat people as killable, gang-affiliated or not, is a goal that may take decades and will require a commitment that is much costlier than any public spending intervention or new legislation. Laws protecting human rights would have to be enforced for all Brazilians, including prisoners. Law abiding middle and upper-class citizens would have to push back and no longer tolerate some of the world’s highest murder rates and jails where 80 men squeeze into a cell built for 20. Transformation this profound would be a difficult message to sell on the campaign trail, but anything less than that sort of social and cultural change from the government and the public will fall short of fixing the deeply rooted problems with Brazil’s prison system.

January 27, 2017

*Andrew Johnson is a Research Associate with the Center for Religion and Civic Culture’s Religious Competition and Creative Innovation (RCCI) initiative at the University of Southern California.