By Ernesto Castañeda

January 11, 2024

Republicans in Congress are denying funding to Ukraine and Israel over migration and border security, but the premises and assumptions used to discuss the issue fail to take the following elements into account.

It is hard to determine if numbers are really without precedent. There has been a change in that immigrants come and turn themselves in to try to come in with a legal immigration status, such as through asylum or the regularization programs available to Ukrainians, Afghans, Cubans, Haitians, Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and other groups. In previous decades, many low-skilled workers knew there were no avenues to enter legally and would try to pass undetected and live undocumented in the United States. That is less common today for so-called low-skilled, recently arrived immigrants. So, an imaginary example would be to count people who once would mainly drive to New York City for the holidays and then compare them to a time when most people would arrive via plane. It would be easier to count the people arriving on planes, but that would not necessarily mean that there are more people arriving now by plane than the ones who arrived driving in the past.

Historically, numbers are not comparable because, before Title 42, apprehensions were counted versus encounters afterward. Previously, most apprehensions would happen inside the U.S., while today, most people present themselves in groups and in a visible manner at ports of entry, along the physical border, or in front of the border wall. Another important difference is that in the past, undocumented workers relied on established family members and networks to get provisional housing and food and find a job. Many recent arrivals may not have close people in the United States and are actively asking for temporary housing and food from city governments. The U.S. does this for refugees and has done it in the past for Cubans and others escaping repressive regimes. Research and history show that these short-term expenses have been good investments, given that refugees and immigrants are more likely than U.S.-born individuals to work, start businesses, and be innovative leaders. Republicans in Congress have denied requests from the White House to provide funding to cities to cover some of these costs.

Some propose detention as deterrence, but prolonged detention in the United States is very expensive and mainly benefits the companies or workers providing and managing detention centers.

A misconception repeated in the media is that most people are immigrating illegally. That is technically incorrect because people are presenting themselves to immigration authorities. Many migrants are applying to legal programs, asking for asylum, or being placed in deportation proceedings.

The situation that we are seeing at the border and some of the solutions proposed indicate some important points that have been rarely discussed,

1) Border walls do not work. Smugglers can cut them, and people can walk around them or come in front of them on U.S. territory.

2) People are turning themselves in, so contrary to what Trump said recently, authorities know where people are from and where they are going. They have notices to appear in immigration court, and they register an address in order to receive notices and updates if they want to continue with their asylum process and regularize their status. In the past, a great majority of people go to their migration court hearings.

3) CBP One appointments are too cumbersome to make, and there are not enough slots available, so people are showing themselves at ports of entry and between them.

4) The parole program for Haitians, Cubans, Venezuelans, and Nicaraguans is working to create a more rational and orderly process. Taking the program away —as Republicans in the Senate want—would make things worse.

5) Putting more pressure on Mexico to deport more people and stop them from getting to the border is unsustainable. Mexico cannot manage the issue by itself unless it gets pressure and funding from the U.S. and international organizations, like Colombia does, to establish immigrant integration programs for immigrants who want to stay in Mexico, and it provides paths to citizenship for them.

Thus, Blinken, Mayorkas, and their companions and team’s visit to Mexico is important. Mexico has been a willing partner, agreeing to take people from third countries under the Remain in Mexico and Title 42 programs, but those programs could only work temporarily. Mexico has also increased the number of deportations. However, deportation only works if people are unwilling to try multiple times. Increasing immigration surveillance, deterrence, and deportation does make arriving in the U.S. harder. It also makes it more expensive and thus attractive for organized crime to get involved in it as a business, thus getting more people to the border once they figure out the business model and logistics even with new policies in place.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has asked for a regularization of U.S. relations with Cuba and Venezuela. There have been positive steps with Venezuela already. This could be a good opportunity to remove Cuba from the list of states sponsoring terrorism, which would reduce some of the emigration pressure in Cuba.

Mexican authorities have disbanded many caravans and slowed the trek of thousands of migrants. Nevertheless, people who are escaping violence and persecution or have sold everything will try to get to the United States.

Long-term ways to address the root causes of migration are to continue providing international aid and supporting democratic institutions. One has to keep in mind human rights. The Mexican Supreme Court of Justice has found that profiling people suspected to be migrants in buses to be unconstitutional. To engage the Mexican Army is not the solution either.

The silver lining is that despite the images we see in the news and seasonal peaks, it is not as if all the world is on the way to the U.S.-Mexico border. Most people want to stay home.

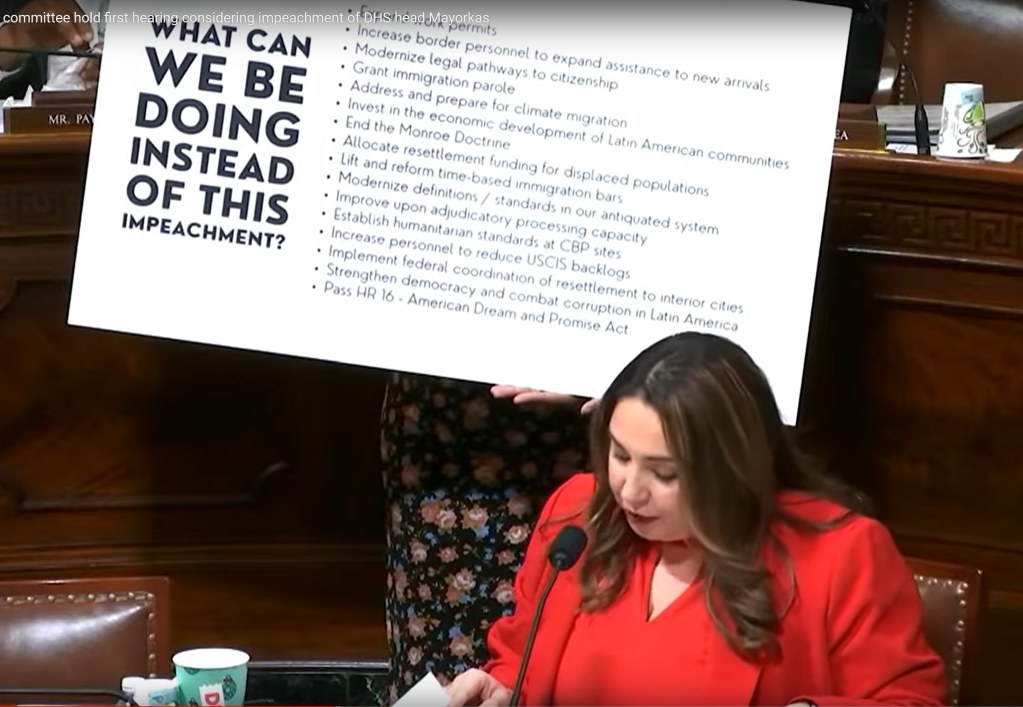

Congresswoman Delia C. Ramirez (IL-03) presenting immigration policies the Congress could be working on instead.

In the January 10 hearing towards impeaching DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, Republicans repeated many myths, cliches, and anti-immigrant talking points but did not propose any sensible solutions. It was remarkable that Democrats in the committee saw the political nature of the exercise, and many offered actual solutions to improve the situation at the border and inside the United States in a way that makes the immigration and asylum processes more humane and above ground.

Ernesto Castañeda is the Director of the Center for Latino American and Latino Studies and the Immigration Lab at American University.

Creative Commons license. Free to republish without changing content for news and not-for-profit purposes.