by Austin Kocher*

Migrants around the world who are seeking asylum in North America and Europe are finding pathways to safety increasingly blocked—not only by physical borders but also by digital borders. The most recent example of this technological obstruction in the U.S. context is the introduction of a smartphone app known as CBP One, which the government has been using since January to manage the flow of asylum seekers at or near the U.S.-Mexico border.

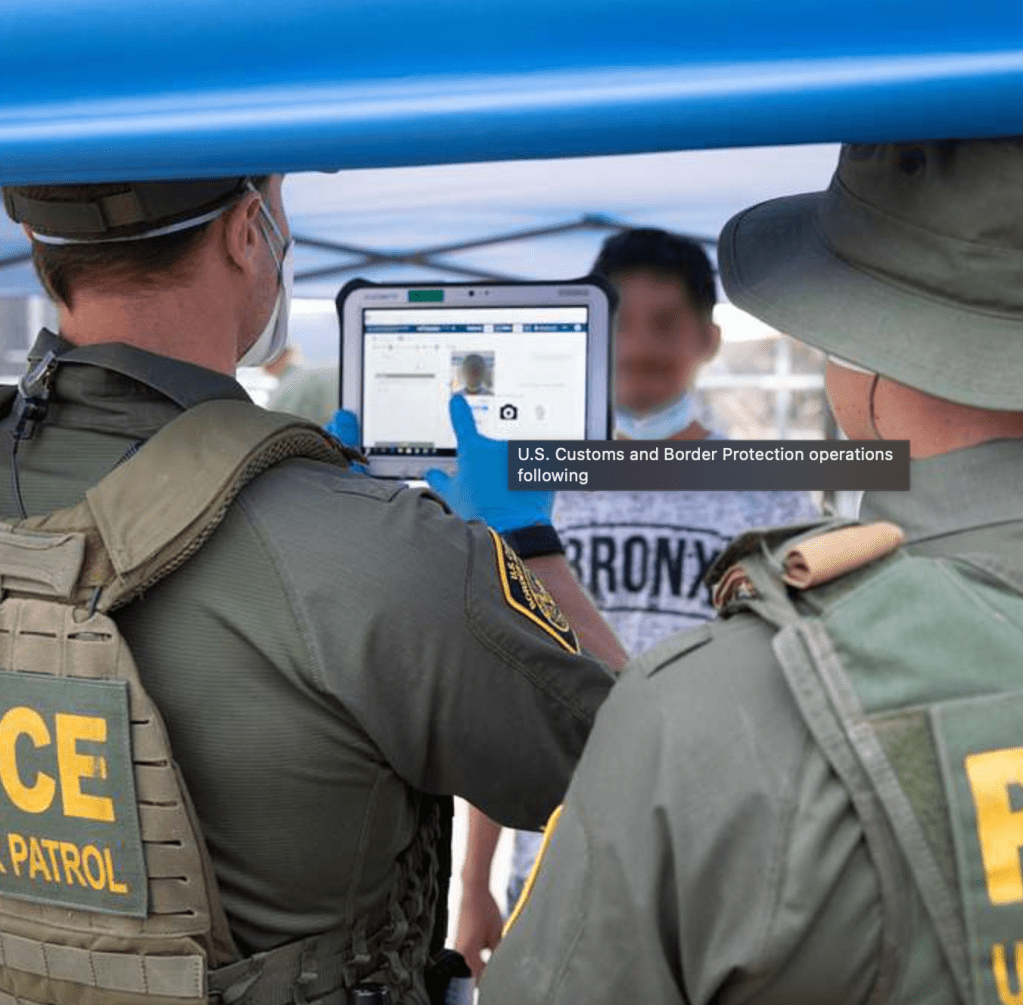

Beginning in January 2023, asylum seekers faced new harsher consequences for seeking asylum directly at ports of entry or crossing unlawfully between ports of entry. CBP required migrants to download the CBP One app onto their smartphones, register their information, and schedule an appointment at a port of entry.

CBP representatives claimed that this would streamline border processing, and for many migrants it did. But for others, the app introduced new digital barriers that reflected old ones: migrants with darker skin reported trouble with the facial liveness test, many migrants did not own newer (and more expensive) smartphones that could run the app well, or access to electricity and the Internet connection. The app disadvantaged migrants who were living at community shelters and camps on the outskirts of border towns in which the Internet was inaccessible.

My recent article on CBP One titled “Glitches in the Digitization of Asylum: How CBP One Turns Migrants’ Smartphones into Mobile Borders,” unpacks the various types of technological hurdles that migrants have faced when trying to use the app, and further attempts to analyze how this app fits within the broader landscape of borders, migration, and technology. But in this blog, I want to expand on those aspects of the digitization of asylum that represent a real concern for the right to ask for asylum going forward.

Specifically, we must think about the larger and longer-term consequences of CBP One for the asylum system writ large. Although CBP One and the current policies surrounding it may be an improvement for many migrants seeking asylum now, the question we should ask ourselves is, how might this app be used in restrictive, dangerous, or capricious ways that could undermine, rather than expand, the United States’ commitment to human rights?

A recent example of this provides some early clues about the fragility of CBP One as a tool.

In June 2023, Customs and Border Protection suspended access to CBP One appointments at the Laredo port of entry in South Texas, effectively (though indirectly) suspending access to asylum itself in that spot. CBP’s rationale appeared to be tied to concerns about migrant safety in Nuevo Laredo, the city on the Mexican side of the border that is among the more dangerous border cities. Immigrant rights advocates reported at the time that migrants who were coming to Nuevo Laredo to seek asylum were being targeted for extortion and kidnapping. That is those presumed to try to present themselves to the appointments they had secured through CBPOne were being asked for money along the route in order to make it to the U.S. border. As a result of CBP’s decision to halt CBP One appointments, migrants would have to travel many miles on perilous roads to the nearest ports of entry that did accept CBP One appointments, such as those in Eagle Pass and Hidalgo, Texas.

A closer look at CBP’s website reveals that Laredo was removed as an official CBP One location late in the day on June 8, although CBP’s website did not make any public announcements related to their decision to suspend access. The lack of public announcement or justification for this decision raises some questions and concerns. While the intentions may have been good ones, could canceling asylum appointments at precisely the moment that migrants were facing increased targeting put them at greater risk for violence? Is it lawful or ethical to essentially switch asylum off and on through an app in this manner?

Immigrant rights advocates appear to share these concerns. Human Rights First published a scathing report that called the Biden administration’s new asylum policy a “travesty,” and pointed out the various additional hurdles that asylum seekers face including challenges to using the CBP One app and the additional risk that migrants face while waiting in Mexico. Amnesty International claims that as part of the new, broader asylum policy, CBP One likely violates migrants’ right to seek asylum. Additionally, a new lawsuit by a number of immigrant rights groups, including the ACLU, allege in their complaint that the challenges migrants face when using CBP One frustrate their attempts to lawfully seek asylum. And yet another lawsuit filed by the immigrant rights group Al Otro Lado at the end of July specifically alleges that CBP One created a “turnback” policy that violates the United States’ asylum obligations.

Indeed, the suspension of CBP One appointments in Laredo in June were an important red flag that reinforce immigrant rights groups’ concerns and presents us with a real-time example of these concerns. Thankfully, CBP reopened access to asylum by the end of June—although, once again, no announcement of justification was provided, leaving the public in the dark about what criteria the agency is using to make these decisions. It is entirely possible that CBP had good reason to suspend the use of CBP One. The app may well present the agency with novel security risks. However, without providing justification for this move or another pathway for migrants to seek asylum, this specific example may foreshadow a new era of on-again/off-again access to asylum that is likely to generate ongoing criticism and possibly even more lawsuits.

None of this should be construed to suggest that the U.S. has been unwavering in its commitment to migrants’ rights prior to CBP One. Rather, the mandatory use of an asylum smartphone app has the potential to both accelerate and further invisibilize the life-and-death authority to decide who gets access to migrant protection (and when and where).

It is not all bad news for CBP One. At the end of June, CBP expanded the number of daily CBP One appointments to 1,450, up from 1,000 in early May, a significant increase. The agency also improved how the app functions, both by issuing a series of software updates and by reconfiguring the way that migrants schedule appointments. Instead of a first-come, first-serve basis, migrants have a full day to enter their information into the system, then the backend system slots migrants into available appointments overnight. These improvements are not trivial and the responsiveness within the agency stands out in a positive way. However, as I say in my article on CBP One, when the question of who has access to the fundamental human right of seeking asylum is answered with successive rounds of glitches and software updates, we have, to quote Alison Mountz, “lost the moral compass of what is at stake.”

* Austin Kocher is a Research Assistant Professor with the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University and a Research Fellow at the Immigration Lab and the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies at American University.